Java is a rather small island compared to giants like New Guinea, Borneo or Sumatra. Yet it is called home by more than half of the Indonesian population : a staggering 145 millions people by 2015.

This is on Java that some of the most powerful kingdoms of the pre-colonial times flourished. And this is also Java that will become the core of the Dutch colonial empire.

This article is the first of a series to introduce to you to the culture of the Javanese people, the main ethnic group of Java island. The second part deals with the religion of the Javanese.

Java and the Javanese

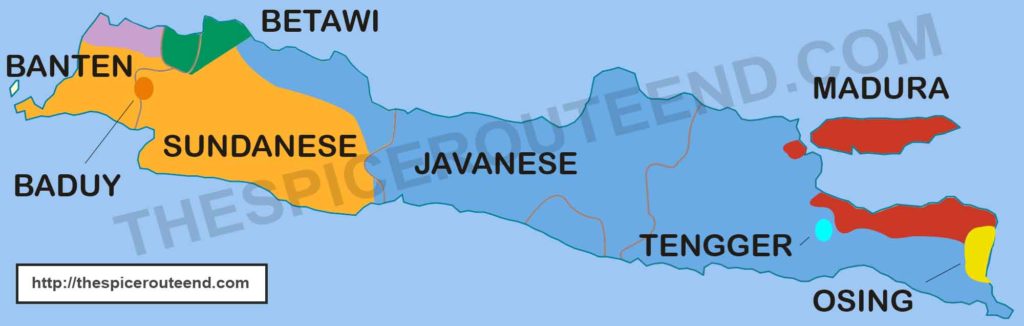

Java is not home only to the Javanese, even if they form the main ethnic group. The Sundanese, the Madurese or the Betawi are other close neighbours, that speak a different language as their mother tongue.

Yet despite clear differences, it is also possible to observe similarities between neighbouring cultures : the traditional Sundanese and Javanese attires are quite close for instance.

To make it simple, the Javanese are the ones that speak the Javanese language. Their homeland is the central and east regions of Java island.

Regional differences

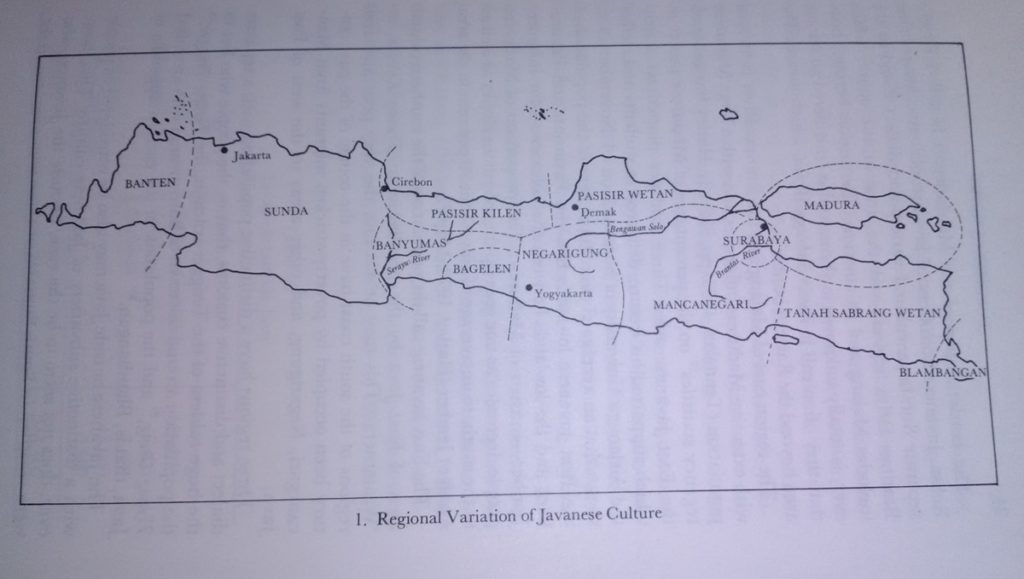

The Javanese recognize some regional particularities (I have extracted the following description from a book written in the 80s : most remain true but deep Islamisation has occurred since 40 years and some comments about the religious norm or the culture might be out of date).

- The negarigung : the region encompassing Yogyakarta and Surakarta (Solo). This is the core of the court civilization of Java that is very proud of its literary tradition and sophisticated art of court as dances and music. The religious life is rather syncretistic.

- The pasisir or the north coast region spanning from Cirebon to Gresik. Puritan Islam is dominant here.

- The town of Surabaya and its surroundings shares many similarities with the pasisir but is often considered a cultural area of its own, with its own dialect.

- The mancanegari (“Outer region’) is the region of East Java bordered by Central Java to the West and Mount Semeru to the East. The towns of Madiun, Kediri and Malang are part of it. The culture here is close to the court culture of the negarigung even there is no more court in this region since centuries.

- Further east, one finds the tanah Sabrang Wetan (‘the area beyond the eastern border). A large portion of the population actually hails from Madura, but in the South (very poor and arid) and on the mountain slopes.

- The regions of Banyumas (and its distinct sub-region of Bagelen) have very distinct dialects, unique life-cycle rituals and particular folklore.

- There are also 3 very unique pockets of population with a separate dialect and distinctive customs : the Tengger who live in the caldera of the Tengger volcano (within which one finds the Bromo), the Osing around Banyuwangi and the Blambangan population on the eastern tip of Java.

A short history of Java

Or more exactly, a short history of the Javanese homeland. I have divided it in 3 phases

Ancient times – 16th century : Hindu-Buddhist kingdoms

For centuries, the history of Java is that of kingdoms that fight for the control of a larger territory. Both Buddhism (under different forms) and Hinduism (from various traditions) prevailed among the rulers that build temples.

Chinese sources and very scarce stone inscription evokes an Hindu kingdom on the north coast of Java (near modern Jepara) around the 6th or 7th century. More solid evidence teach us that a Saivite king called Sanjaya established himself in the valley of the Merbabu and Merapi volcano (north of modern Yogyakarta) in the first half of the 8th century. The remains of a temple complex on Dieng plateau are dated from this period.

From left to right : Mount Merbabu, Merapi, Sumbing, Sindoro (the tip of Mount Andong can also be seen left of Merbabu)

Candi Arjuna, a Shiwaist temple from the 8th century (Mataram kingdom)

The center of power shifted several times through history back and forth from central to east Java : the old Mataram kingdom was most likely based north of Yogyakarta (where the temples of Borobodur and Prambanan have been built), then the power moved to Kediri and the valley of the Brantas river before settling again near the river delta (probably near the modern town of Trowulan south of Surabaya).

Singosari temple

Candi Sukuh

Candi Belahan

A Javanese civilization emerged and developed a sophisticated artistic, literary and religious culture.

The apogee of this era is reached with the Majapahit kingdom (14th until early 16th century) that came to dominate the central and eastern part of Java, Madura and Bali. Through expeditions, it also had a punitive influence over western Java, some parts of south Borneo, Sulawesi, Sumbawa and the Straits of Malaka (interesting article if you want to go further).

The heritage (often fantasized) of Majapahit will latter be claimed by Indonesian nationalists : “the vision of Javanese paramountcy over the islands that inspired the rulers of Majapahit, and which is enshrined in the term nusantara, has in modern times been realized to a degree far beyond the capacities of those rulers. In the 20th century, Majapahit became the historical model and legitimation for the dreams of the Javanese leaders” (The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia).

It’s worth noting that besides temples and some texts that mostly deal about the elite and the religion, few things have survived unaltered from this era. For instance, the keraton (courts) of Yogyakarta and Surakarta will be founded only in the 18th century (even though they claim the heritage of the former court cultures).

14th – 16th century : the advent of Islam

The history of the early days of Islam in Java is still not fully clear to this day. Unless new significant historical sources are discovered, it will probably remain so.

By the 14th century, Java was shared between interior kingdoms producing rice in fertile valley and port-town engaging in regional trade.

We know than from the 7th century, Muslim emissaries from Arabia began to arrive at the Chinese court. In the 9th century, thousands of Muslim merchants could be found in Canton. Such contacts were possible through maritime transports and the sea routes pass through what are now Indonesian waters.

So Java was probably exposed from an early period to Islam, most likely through merchants (potentially from Arabia but also in large parts from South India or Persia).

It would sounds logical to find the first trace of Islam on the coast but actually the first conclusive evidence of Islam among the Javanese are gravestones near Trowulan (the supposed capital of Majapahit, so an interior kingdom) dated from 1368-69.

In the early 15th century, Chinese observer Ma Han did not describe Muslim presence on the north coast (the pasisir). A century later, when the Portuguese Tome Pires visited the coast in the 1520s, Islam has established.

In the early 16th century, Islamic states had been founded in the port towns of the pasisir : Gresik, Tuban, Demak … “Most of these were led by Muslims of foreign origin, who were accomodating themselves to the cultural style of the Hindu-Buddhist Javanese aristocracy and were thereby becoming Javanese” (Ricklefs, Polarizing Javanese society).

In 1527, Islamized kingdom of Demak attacked a highly declining Majapahit and destroyed it. The royalty and many members of its aristocracy were probably killed, while others fled to the still Hindu-Buddhist kingdoms of eastern Java and Bali (where there were Javanese courts). Demak expanded to the east but was stopped by the Hindu state of Panarukan (East Java). For the first time, a Islamic kingdom came to dominate, for a short time, Java.

But quite shortly after (second half of the 16th century), the power shifted back again to the interior of Central Java, with the expansion of a former Demak vassal in Pajang (near present day Surakarta), that would be in turn taken over by a new kingdom of Mataram led by Senopati in 1588. He returned to the land of the ancient kingdom of Mataram (that had built Borobodur 600 years before !) and established his court in Kota Gede (modern Yogyakarta).

16th to 18th : the last great Javanese kingdom

“Mataram court was still very imperfectly Islamised. Its literary traditions, its rituals, its very calendar, were still substantially Hindu-Buddhist in character” (Ricklefs, Polarizing Javanese Society).

Mataram adopted an ambivalent attitude towards Islam :

- Under Sultan Agung (r. 1613-1646), a major reconciliation of Javanese royal and Islamic traditions was undertaken (alliance with the Muslim rival princely line of Surabaya, conversion of the Javanese-Hindu Saka calendar into a Javanese-Islamic hybrid lunar calendar, import of Islamic inspiration in the court culture literature…).

- But Agung’s son Amangkurat I (r.1646-1677) also commanded the slaughter of 5’000 Muslims clerics and their families on the great square before the court.

In the meantime, new actors established themselves in Java : the Europeans. The VOC had erected its fortress of Batavia in 1519 on the site of modern Jakarta. Java is then the largest rice exporter of South-East Asia (it will remain so until the 19th century) and is located right in the middle of the spice route that is thriving.

Sultan Agung (that has attempted but failed to take over Batavia twice in 1628 and 1629) is largely regarded as the last great Javanese king. From his death in 1646, the Javanese land will experience a period of almost constant warfare for the throne of Mataram.

The most bloody episodes are the rebellions against Sultan Agung’s son between 1675 and 1679, then the 3 sucessive Javanese Wars of Succession (1704-1708, 1719-1723, 1746-1757).

The VOC involved itself in those feuds, the ailing heir of Mataram calling for help against rebels. “The Dutch had sought stability by maintaining a king on the throne of Mataram who would rule all of Java in their interest. They had found instead of enjoying the profits of stability, they were constantly fighting wars on behalf of the kings whom they supported, at a crippling cost to themselves” (Ricklefs, Modern History of Indonesia).

The Dutch nonetheless traded their support for privileges. In 1743, the north coast of Java was fully leased to the VOC that ruled it alone, controled the ports and regulated trade.

In 1755, another rebellion cut the kingdom of Mataram in two : prince Mangkubumi revolted against Pakubuwana III (that had moved his court from Yogyakarta to Surakarta in 1746) and proclaimed himself Sultan Hamengkubuwana I of Yogyakarta. Mataram would eventually be split in 4.

Keraton Yogyakarta

Keraton Surakarta

The colonial era (18th – 20th century)

The Sultanates of Yogyakarta and Surakarta that have survived until today are thus the direct heirs of Mataram kingdom. But from their inception they were under the domination of the Dutch.

In 1799, the VOC had gone bankrupt (mostly due to the costs of leading war in Java) and its possession were transmitted to the Kingdom of Holland. This is the official start of the colonial era in Indonesia.

In 1825, prince Diponegoro revolted and engaged a 5 years war with the Dutch. Java was eventually pacified. 1830 marked the effective start of the colonial rule in Java.

Soon the colonial government recruited the now idle aristocracy to populate the rank of its administration as clerks or teachers.

The submission of the Javanese aristocracy by the Dutch had a long-lasting effect on their prestige. In 1873, the last court poet of Surakarta R. NG. Ronggawarsita wrote that kasekten (magical power that was detained by the ancient kings of Java) was now lost.

From 1830 to 1860, the colonial state imposed the so-called Culture System, in which the Javanese peasant had to supply agricultural commodities (such as sugarcane, indigo, tobacco, tea …) to their rulers.

Towards the end of the 19th century, the Dutch rulers introduced more educational opportunities for the local populations.

In the early 20th century, the first major Indonesian civil organizations were all founded in Java : Budi Utomo in 1908, Sarekat Islam in 1911, Muhammadiyah in 1912, Nahdlatul Ulama in 1926…

After the short Japanese rule during the WW2, Independence of Indonesia was declared on 11 Augustus 1945, but the modern Republic of Indonesia would be effective only in August 1950 after a bitter conflict with the Dutch trying to retake control of their former colony.

After independence, Indonesia was politically divided between Nationalists, Islamists and Communists. This will eventually led to a coup in 1965 when the army took power and slaughtered afterwards hundred of thousands, potentially millions, of communist supporters.

The army, in the person of general Suharto, will keep the power until 1998.

In 1998, the regime of Suharto (the New Order) fell and a new democratic era opened.

The Javanese language

Tablets of stone or metal as old as from the 8th century have been found in East Java by archeologists. They are written in an ancient form of Javanese that uses a script derived from an old Indian sanskrit script called the Palawa script.

This script evolved a lot through the centuries but remained the basis of the modern Javanese script. Yet, Javanese is nowadays mostly written in latin script and the younger generation have often lost command of the Javanese script.

Javanese is a also a complex hierachical language with different forms : the lower ngoko and the upper krama and krama inggil. If the ngoko is spoken as their mother tongue by tens of millions of Javanese, the mastery of the upper registers of Javanese has declined in the recent decades.

As everywhere in Indonesia, if the use of the local language is tolerated during the first years of elementary schools, all the teachings are conducted in Indonesian afterwards.

The Javanese litterature

The most ancient works of Javanese literature that have survived to these days were actually found in Bali and Lombok :

- The famous Nagarakretagama poem from the 14th century that describes the glory of Majapahit was preserved as a palm-leaf manuscrit (lontar) that Dutch soldiers seized in the late 19th century during their attack of the Cakranegara royal house of Lombok.

- Another famous poem from the Majapahit era, the Sutasoma was preserved on lontar in Bali for centuries.

But older piece of Javanese culture had passed through the centuries via the oral tradition of the shadowplay (wayang) and myth telling (lakon).

- Historians believe that the two major sanskrit epics of Ancient India, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, were translated and adapated in Javanese under the Medang and Kediri kingdoms (9th-11th century).

- Typical Javanese characters were added to the Indian ones : the clown-god Semar and his sons (Petruk, Gareng, Bagong). Together they are called the panawakan.

- The stories cycle around the mythical prince Panji are also anterior to Majapahit.

The Javanese litterature was revived under Mataram through royal chronicles (like the Badad Tanah Jawi) and more general books like the Serat Centhini whose detailed description of the Javanese daily life is often considered as an encyclopedia of the Javanese culture.

The Javanese courts historically sponsored royal poets. Poem reading and singing was a recognized form of art (tembang).

In the modern era, Javanese writers, as other Indonesian ethnic groups, largely abandonned the Javanese language to the profit of Indonesian. Major novelists from Java such as Pramoedya Ananta Toer or Ahmad Tohari made such choice.

Javanese art

The Javanese developed over the centuries a rich artistic tradition that can be splitted in two :

- The “higher” art complex that came to be essentially associated to the courts of Java (today Yogyakarta and Surakarta).

- The “lower” popular arts.

Other key “visual aspects” of the Javanese culture are the joglo architecture as well as the art of wax and dye textile (batik).

Some piece of cloth are also very closely associated to the Javanese : such as the women kebaya shirt or the male blangkon headdress.

The arts of the court : wayang, gamelan and dances

The Javenese shadowplay (wayang) is internationaly known as a striking feature of the Javanese art. The puppeteer (dalang) tells myths (usually from the Javanese version of the Mahabharata or the Ramayana) by acting, singing and the song of gamelan (Javanese percussion orchestra) accompanying him.

The Javanese courts also had a long tradition of dances (djogèd). The most ancient ones were the princess dances performed only by young girls (srimpi and bedhaya). Later came the wayang wong dances for both sexes that acts out the wayang stories.

The court dances tends to be rather abstract. The rythm is slow and controlled, the posture must be absolutely still and perfect, breathing unoticeable, eyes kept fixed in one place. The esthetic ideal is that of controlled motion, of perfect self-contained grace.

A key concept in the ethic of the Javanese aristocrats (the priyayi) is the opposition between alus (subtle, refined, civilized) and kasar (impolite, rough, uncivilized).

“The ascent from the uncivilized animalstic peasant to the hyper-civilized divine king takes places not only in terms of greater mystical achievements, more and more highly developed skills of inward-looking contemplation and refinement of subjective experience, but also in greater and greater formal control over the external aspects of individual actions, transforming them into art or near-art.

In the dance, in the shadow-play, in music, in textile design, in etiquette, and, perhaps most crucially of all, in language, the aesthetic formalization of the surfaces of social behavior permeates everything the alus Javanese does” (Geertz).

Popular folk arts

Despite being patronized by the Javanese elite, wayang shows were pretty commonsight in Javanese commoners home until more or less the 70s. They were typically given for special occasions like wedding or circumcision. In the 50s, the family and the guests of the host giving the wayang would usually sit in front of their house on the shadow side, while a crowd of uninvited guests would gather to watch the dalang work on the other.

Several form of art were also very popular as public entertainment. We can think about popular theatre such as kethoprak, ludruk (popular farces), reyog (mask dance performance in which performers enter trance) jaranan (dance performance involving bamboo model horses and spirit possession)s or tayuban (lascive Javanese female dances).

Another specific set of Javanese arts was cultivated in the traditional Islamic boarding schools (pesantren) : we think immediately about the indigenous martial art pencak but also some forms of music such as terbangan (elaborated chanting inspired from Persia) or gambusan (Middle-Eastern type of orchestra with string instruments).

Decline of traditional Javanese art

Ricklefs observed that in the last 2 decades of the New Order [80s and 90s] : “in general, once-widely spread Javanese arts such as gamelan, wayang, kethoprak, ludruk, reyog, jaranan, tayuban and so on – those shadow plays, masked dances, masquerades, horse-dance, youth dance performances, male group dances, village dancing and singing women, and suchlike, many of them described by Pigeaud in great variety in the 1930s – were becoming less common and, where they survived, they were losing much of their older spiritual and supernatural aspects and were subjects to more Islamic norms.”

Already in the 50s, Geertz had noted that the art form associated with the courts (in particular wayang) were losing popularity among the masses to the profit of movies for instance. The priyayi were left as the main patrons of traditional arts (a situation quite similar to that of opera or classic music in Europe).

Since 1924, the Sultan of Yogyakarta has been sponsoring the Habirandha school for wayang puppeteers but the number of students enrolling and graduating is diminishing every year. Wayang wong is still performed at the Sriwedari theatre in Surakarta but the audience are small.

Besides the simply lack of public interest, a huge cause behind the decline of popular form of folk arts was the anti-Communist campaign after 1965. The Indonesian Communist Party had supported and associated himself to popular theatre (kethoprak, ludruk, reyog …) for propaganda purposes. Many members of the troups, most of them affiliated or at least sympathetic to Communism, were arrested or even killed in between 1965 and 1966. The others were left under constant surveillance and pressure from the regime in the fear of a Communist Revival.

“There were some attempts to modernize and Islamise various art forms, but they had patchy success. Meanwhile all of these forms were threatened by the spread of television, modern films, electronic games and in some cases – notably wayang – by the rising cost of performing them“.

“Modern forms of theatre also evolved in this period and sometimes adopted explicitly pious Islamic styles and themes. But this, too, enjoyed mixed success. One common problem was a degree of discomfort – sometimes indeed downright hostility – among pious Muslims to artistic performances of almost any sort“.

“The village abangan art form that Muslim proselytisers in Java most hated was tayuban – the enticing dance by women, inviting men to join them, often accompanied by drunkenness, prostitution, and veneration of local spirits. Muhammadiyah had always opposed tayuban and by the 1950s had effectively stopped it in Javanese towns and cities” (Ricklefs, Islamisation and Its Opponents).

Javanese Culture Series

Javanese Culture – Religion and beliefs

Javanese Culture – History, People & Art

Sources

- C.Geertz – The Religion of Java (1960).

- Koentjaraningrat – Javanese Culture (1985).

- Andrew Beatty – Varieties of Javanese Religion (1999)

- B. Anderson – Language and Power. Exploring Political Cultures in Indonesia (reprint from 1990).

- M.C. Ricklefs – Polarizing Javanese Society. Islamic and others visions (c.1830-1930) (2007)

- M.C. Ricklefs – Islamisation and Its Opponents in Java (c.1930 to the Present) (2012)

- M.C. Ricklefs – A History of Modern Indonesia Since C.1200 (4th edition, 2008)

- N. Tarling – The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia : Volume 1, From Early Times to c.1800

I compiled a general bibliography about Indonesia in this article.

Please edit your map language of java island Using/balambangan, banten tengger are part of Javanese langugae same as ngapak,matraman,arekan(timuran),etc

I think baduy/kanekes still a part of Sundanse language