- Part 1 – the facts : half of Indonesia rainforests have disappeared since WWII

- Part 2 – the causes : 50 years of unsustainable forest ressources management

- Part 3 – analysis : What did Indonesia won from that ?

- Part 4 : the future : current trends and policies

- I want to keep myself informed about the recent developments, what should I read ?

- Notes

When hearing deforestation in Indonesia, it’s likely that you have associated it to palm oil production.

Now have a look on this chart, that shows forest loss measured within and outside industrial concessions (other factor part) :

Even if you could magically make oil palm plantations disappear in Indonesia, you would be far from solving the deforestation issue ; although you would significantly improve the situation, especially in Kalimantan.

Deforestation in Indonesia is actually a complex process ongoing since at least 50 years, at the crossroads of economical, political and society issues.

I have tried in this article to go beyond cliché (palm oil bad) and by looking precisely at economy and history to paint an actual and balanced picture of the evolution of Indonesian forests.

Warning : this article is quite long (about 11,500 words long or 23 pages).

Part 1 – the facts : half of Indonesia rainforests have disappeared since WWII

One of the world largest and richest rainforest

Within the political boundaries of modern Indonesia lies the 3rd largest span of tropical rainforest in the world, after Brazil’s and Democratic Republic of Congo’s.

Tropical rainforest is the most diverse ecosystem found on Earth.

This statement is wonderfully illustrated by the staggering statistics of Indonesian biodiversity. While the archipelago represents only 1,3% of the Earth’s surface ; it is home to 11% of all the world’s known plant species, 10% of the mammals and 16% of the birds (FWI 02).

Keep nonetheless in mind that the archipelagic nature of Indonesia that contributed to generate a high number of endemic species also pushes the number up.

Based on the climate and the topography, it is reasonable to assume that Indonesia was almost entirely forested in ancient times (MacKinnon 1997).

Hence Sumatra or Borneo islands (where most of the deforestation is concentrated) used to be close to an immense single rainforest, roamed by tens of thousands of orangutans, tigers, rhinos and elephants as well as millions of smaller primates, mammals, birds, reptiles, insects …

In 1784, irishman William Marsden then established in Bengkulu described Sumatra as “an island which strikes the eye as one general impervious, and inexhaustible forest“.

This statement probably remained valid until quite recently. Even overpopulated islands of Java and Bali were until the early 20th century home to 2 endemic species of tiger. In 2019, wild rhinos and leopards can still be found in specific areas of Java.

From a sparsely populated archipelago to a demographic behemoth

One very important data to keep in mind is that Indonesia’s population remained quite low until roughly WWII.

The first reliable global census of the population of modern Indonesia was carried out by the Dutch colonial administration in 1930. Back then, Indonesia population was 61Mio inhabitants, of which 42Mio people lived on Java, hence leaving only 20Mio people to inhabit the forest rich islands of Borneo, Sumatra, Sulawesi and Papua (also called “outer islands” in the past) (source).

As per 2010 census, Indonesia population had reached 237Mio inhabitants and is expected to top 300Mio by 2035. Even if most of the population is now urbanized, this had a deep impact of the demand for agricultural land and natural resources.

The major shrinkage of natural forest since the 70s

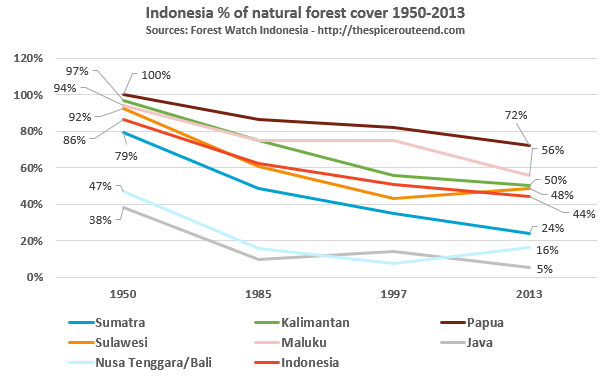

Let’s now have a look at the brutal numbers. I compiled data from various sources (see notes at the end), hence some inconsistencies (improvements in forest cover are likely to be the result of incorrect historical data rather than reforestation). Precisely measure deforestation has proven a very difficult task since more than 50 years, only becoming slightly easier with the advent of satellite imagery.

Natural forest refers to primary and secondary forests but excluding timber or crop estate plantations. All the numbers are estimates, but the trend is very clear.

There are 2 ways to look at this chart :

- Indonesia has lost nearly half of its natural forest cover in 63 years (800,000 km2). This is larger than the entire Turkey or Mozambique.

- Indonesia still have 44% of its territory covered by natural forest ; which is still quite a lot. Biodiversity has suffered heavily, with many iconic as well as less-known endemic species now critically endangered, but not all hope is lost.

For the record, according to the Indonesian Forestry Law (UU 88 41/1999 art. 18) to sustainably manage the forest, a minimum of 30% of the total land of an island has to remain naturally forested.

Introducing granularity in the definition of forest

It’s important to understand that “forest” can refer to many things. Actually neither the different levels of government, nor the scientists themselves agree on a common and precise definition. Some vocabulary is nonetheless necessary to understand what we are talking about.

Condition of the forest : primary and secondary

Forest that has never been disturbed by men is usually called primary forest. The terms “old-growth forest” or more poetical “pristine forest” are also used.

Forest that has been partially exploited (usually for selective logging) is referred to as secondary forest or “logged forest”. It usually implies that ‘logging roads’ have been open through the forest to access the most valuable trees.

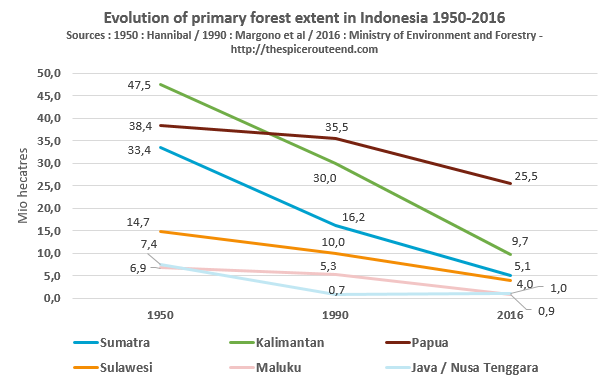

The following chart highlights the degree of exploitation of the Indonesian forests since 70 years :

When primary forest disappears it doesn’t necessarily mean that it has been converted for agriculture. Most likely, the forest now stands as secondary forest.

Nature of the forest : based on altitude and type of soil

Forests can be very diverse depending on their environment. Each type of forest is home to specific plants and trees that provide an habitat for different kind of animals.

In Indonesia the main types of forests are :

- Lowland forest (below 300m of altitude)

- Upland/Submontane forest (between 300 and 1000m of altitude)

- Montane forest (above 1000m)

- Peat forest (swampy environment)

- Mangrove

Lowland forests are more easily accessed and their topography and soil fertily are most favourable to agriculture and human settlements. They are also the most biologically diverse ecosystem.

Indonesia may have preserved more than 40% of its forests but a large share of it is located in upland or montane landscape.

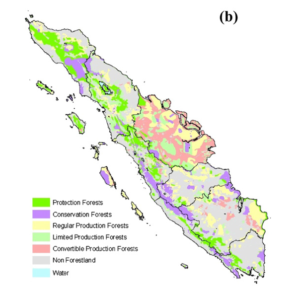

Legal status of the forest

Virtually all the forests of Indonesia are under the responsability of the Ministry of Environment and Forestry (Kementerian Lingkungan Hidup dan Kehutanan or KLHK). Very few forests are truly privately owned, the rest is allocated through a system of concession.

The most common land-use allocation is production forest (Hutan Produksi or HP, HPT for limited production forests). Conservation forests (Hutan Konservasi or HK) are protected to preserve their ecosystem and the biodiversity (they can be part of a National Park but several slightly different status also exist) while protection forests (Hutan Lindung or HL) are protected for hydrological reason (mainly preventing floods and erosion).

The Ministry is also able to designate some area as convertible production forest (Hutan Produksi yang Dapat Dikonversi or HPK) , which is a transitional status before the issuance of a licence for clearing the forest and establish a timber (usually fast growing acacia) or estate crop (mostly oil palm) plantation.

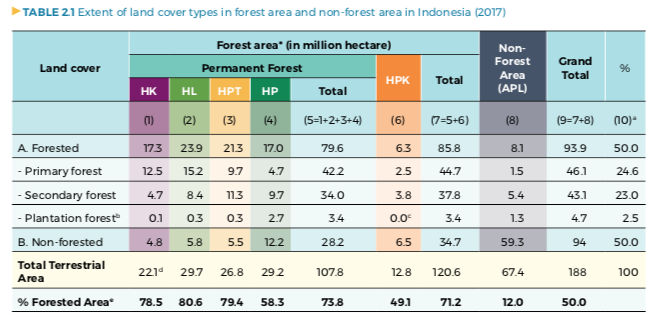

The following table is the government summary of the situation.

One important precision when you read a government report : forest land means that the land is under the control of the Ministry ; it may be not have a forest cover. For instance, the table above indicates that 4,8Mio ha of forest land protected for conservation value are actually not forested !

Another interesting reading is that licenses for clearing and conversion have already been issued for 2,5Mio ha of primary forest (about 5% of it).

Part 2 – the causes : 50 years of unsustainable forest ressources management

So the legitimate question at this point is : what happened to the forests ?

Indonesia’s population has exploded but the country was also very large. Individual farmers took their share in the deforestation process but the largest culprits were industrials.

The easiest way to untangle the intricate web of causes is to review the recent history periods by periods.

The 70s : the wild logging boom

One of Suharto’s key economical policy

The story starts at the end of the 60s. Indonesia is still approximately covered at least at 70% by pristine forests but is also very poor and underdeveloped (income per capita of about $50).

In the wake of the events of the 30th September 1965, independence hero Sukarno loses its control over the country. From March 1966, General Suharto assumes political authority. He will keep it until 1998.

One of the first move of New Order’s (Suharto regime) policymakers is to develop a national logging industry.

Besides the obvious economical benefits, this policy also serves the purpose of consolidating Suharto’s own power. By granting logging concession rights to its cronies, he could reward and control them.

- In May 1967 the government passes the Basic Forestry Law (Undang-Undang Dasar Kehutanan) establishing the legal basis for the new timber industry, in particular state control over 74% of the country’s land defined as Forest Area (Kawasan Hutan).

- In 1970, the regulation No. 21/1970 concerning forest concessions is issued. The regime starts to grant selective logging concessions (Hak Pengusahaan Hutan or HPH).

This is the beginning of a huge boom of the timber industry in Indonesia. By the end of 1970, 81 concessions had been allocated to private investors. Foreign companies (like Georgia Pacific or Weyerhaeuser) provided 80% of the capital but were systematically associated to a local “silent partner”, in particular military interests (through a company owned by a high-ranking officer but also foundations or pension funds of whole commands).

From 1967 to 1977, the yearly output of logs cut exploded from 4Mio m3 to 28Mio m3 (Romm, 1980). By 1979, Indonesia is the world’s leading producer and exporter of tropical logs (tropical wood has special qualities and buyers pay a premium for it) with 41% of global market share.

The rotten core of the Indonesian logging industry

On paper, this sounds like a good plan : Indonesia had 2 of the largest forests in the world on the islands of Sumatra and Kalimantan (the Indonesian part of Borneo). Both islands were close from the Asian markets and rich with millions of some of the most valuable hardwoods on earth like ramin or meranti (dipterocarp family).

Well managed, a logging concession can produce wood indefinitely. Only specific areas are partially logged each year. By leaving the youngest trees untouched and replanting what has been cut, the forest is supposed to remain in good condition. From the very start, Indonesian forestry law included such regulations.

But the proximity between the regime (who granted concessions) and the operators (its cronies) would result in an abysmal lack of oversight and transparencies. The Suharto family alone controlled more than 4,1Mio hectares of concessions (Indonesia Corruption Watch).

Concessions were granted as rewards, not as long-term investments. Over-exploitation was the standard way to operate. Way too much timber was fell for the forest to recover. The greed of the operators left millions of hectares severely degraded even though Indonesian law mandated that logging concessions must remain a permanent secondary forest.

Common illegal practices in concessions included :

- Cutting protected trees, cutting outside the designated cutting block (the area allocated for exploitation each year), cutting tree smaller than the felling limit (50cm), harvesting more than the annual allowable cut.

- Failing to replant 2 years after logging, replanting with low-quality species.

- Removing trees from rivers and stream bank (called riparian forest and normally excluded from exploitation even within a concession), building bridges by pilling up timber logs (which clogs water channels), building substandards logging roads without drainage systems, leading to erosion and landslips.

As of June 1998 (the end of the New Order) 16,6Mio ha of forest land were degraded out of the 69,4Mio ha allocated to HPH (Kartodiharjo & Supriono 2000). Based on Ministry of Forestry data (quoted in Barber 2002), in 2000 55% of allocated concessions were exploited and half of the exploited portion had been abormally degraded.

Over-exploitation doesn’t mean that the forest is cleared. In the most severe cases it might have been reduced to scrubs and generated serious disturbances to its animals populations but forests were still there. Left to recover long enough, degraded forests could have regenerated themselves.

Summary : Suharto’s regime (1966-1998) has launched a furious logging boom in the 1970s that caused serious damages to Indonesia’s vast forests due to over-exploitation and lack of oversight.

1980-1998 : timber industry consolidation

Development of an integrated wood-processing industry

Let’s move forward about 10 years later, we are now in the early 80s. In the previous decade, Indonesia’s economy has experienced significant economic growth thanks to the logging industry and even more importantly to the simultaneous oil & gas boom.

Suharto’s regime decides, quite logically, that Indonesia will be better off if it stops exporting lower-value unprocessed logs and develops value-added products instead.

Its first priority will be the development of an internationally competitive plywood industry in the early 1980s, which will soon experience sensational growth. On the long run, the pulp and paper industry would become the leading wood-processing activities in Indonesia but it would pick up later around the late 80s . Both sectors will receive large investments to build factories and processing mills.

The production of plywood rose from 0,62Mio m3 in 1979 to 4,9Mio m3 in 1985 and 10Mio m3 in 1993 (Barber 2002). For a few years, Indonesia’s plywood producers even formed a cartel (Apkindo) that was strong enough to impose higher prices on the global market.

To stimulate downstream investments, the regime announced in April 1981 that the export of raw logs will be progressively phased out. The full ban would be enforced from 1985 (and is still valid today, as well as the export of sawnwood since 2004).

The export ban will initiate a deep reconfiguration of the industry. Most initial foreign investors were reluctant to invest downstream and many sold their share of the logging business to their domestic partner who had grown very rich by then. By mid 1990s, five large timber companies (Barito Pacific, Djajanti, Kayu Lapis Indonesia, Alas Kusuma and the Bob Hasan Group) controlled 18,5M ha or 30% of the country logging concessions (FWI 2002)

This evolution doesn’t mean than the frenetic development of the logging concessions had come to an halt. By 1980, 519 concessions were operating over 53Mio hectares (Barr, 1998) [Indonesia is about 188Mio ha large]. By 1998 the numbers had reached 651 concessions and 69Mio ha (Kodjo, 2000).

From 1980 to 2000 researchers have estimated that more round wood was harvested for the island of Borneo alone (so also including the Malaysian part) than from Africa and the Amazon combined (Brookfield & Byron, 1990)

Huge industrial overcapacities fueling the logging frenzy

An official from the Ministry of Forestry declared in 2000 that “the wood-processing industry has been allowed to expand without reference to the available supply of timber, resulting in vast overcapacity. The shortfall in the official timber supply is being met largely by illegal logging, which has reached epidemic proportions” (International Herald Tribune, February 1st 2000, quoted in FWI 2002).

It could have been quite simple : the Ministry of Forestry had the list of logging concessions. By law each concession is allowed an annual cut ; so it was obviously feasible to determine the maximum yearly legal timber supply and to regulate the licenses timber-processing plants accordingly.

In the late 90s, the wood supply of the industry was estimated to be sourced 50% illegally, 17% through the legal clearing of natural forests and 33% through timber plantations (FWI 2002).

Industrial timber plantation (Hutan Tanaman Industri or HTI) have been promoted by the government from the mid 1980s as an alternative to logging of natural forest. But with such an oversupply of cheap wood (mostly illegal) available, the profitability of standalone HTIs was rather hypothetical. On top of that business interests are going to completely rig the government policy.

The shortcoming of the timber plantation policy

By law, HTI can only be established on degraded lands, like in the overexploited sections of a logging concessions. A clearing license (Izin Pemanfaatan Kayu or IPK) is then issued and the land can be fully cleared and then re-planted.

But like for logging, rules were going to be rigged in a large extent :

- In 2000 it was estimated that 20% of HTI concessions had been productive natural forest before conversion (Kartodihardjo & Supriono, 2000).

- Still in 2000, only 23,5% of the land allocated to HTI were actually planted according to Ministry of Forestry.

The main reason for that is that a majority of HTI plans were only a cover up to benefit either from subvention or from the associated clearing license.

In 1989, the government introduced the Reforestation Fund (Dana Reboisasi), a volume-based levy collected on timber harvested from logging concessions. The funds were then used to subsidize the establishment of HTI and provide zero-interest loans.

On many occasions, companies have applied for the scheme, published a fake plan, pocketed the subsidy, cleared a logging road, got the most precious timber and stopped operating. An alternative was to stock the plantation with the poorest seeds available.

For these reasons, the production of HTI has always been quite low and lagging far behind the actual industrial installed capacities.

Besides the obvious argument of corruption, government was also facing a dilemma at this time :

- The mindset of the policymaker was that there was still plenty of forest standing (80% of Kalimantan which is huge for instance). And anyway, forest had a very low value if not exploited.

- Indonesia’s economy was already highly reliant on the foreign exchange revenue generated by the timber-based industry. Villages had been built near logging concessions for the workers who were now living in remote areas without any work available as concessions were overexploited.

- The quantity of degraded land was increasing quickly in HPH. Instead of regulating this sector, the government saw the HTI as compromise solution. HPH are by law an asset able to produce wood undefinitely ; unless they are degraded to the point that it’s not possible to harvest timber anymore. The HTI scheme was a way to turn something that has been destroyed into an investment opportunity.

Rampant illegal logging

Given the huge shortcoming in the availability of legal timber, illegal timber brokers flourished. As stated by the Ministry of Forestry in a 2000 report (quoted Barber 2002) :

“Illegal logging has come to constitute a well-organized criminal enterprise with strong backing and a network that is so extensive, well established and strong that it is bold enough to resist, threaten, and in fact physically tyrannize forestry law enforcement authorities…. Illegal cutting occurs in concession areas, unallocated forest areas, expired concessions, state forestry concessions, areas of forest slated for conversion, and in conservation areas and protected forests”.

Besides the emerging criminal actors, low-scale logging was carried out by local communities, despite its ban in 1971 by Suharto. The regime never managed to prevent it.

Summary : even though logging concession were alarmingly damaging forests, the government encouraged the expansion of the wood-processing industry without any further regulation.

Plywood, pulp & paper and other wood-processing industries never developed a sustainable supply of raw wood but instead relied on the never-stopping clearing of natural forest

Late 1980s : the new kid in the block : oil palm

Already in the 60s, Sukarno government with the assistance of the World Bank had invested in state-run palm oil companies. Until today, the Indonesian state operates large palm oil plantations through state-owned companies.

But the private plantations sector truly started to develop in the mid-80s, along with pulp & paper industry.

Both industries expanded aggressively at the expense of both primary and logged forest, taking advantage of the government regulation allowing the clearing of land for the establishment of plantations :

- As we have shown in the last part, wood-processing industry relied heavily on the clearing of forest to supply its raw materials. A few timber plantations were established but far from what was needed.

- Palm oil developers were also very eager to establish on forest land : it is more fertile than degraded land (that needs initial investments to be rehabilitated) and land clearing is a great opportunity to make hefty profits by selling the timber to factories (as high as 2’100$/ha)

Oil palm plantations grew from 106’000ha in 1967 to 606’000ha in 1986 and 2,5Mio ha in 1997 (Kartohidjo et Supriono 2000). By 2004 it was 5,2Mio ha and 9,4Mio ha by 2013 (FWI 2013).

Indonesia became world’s leading palm oil producer in 2008, outpacing Malaysia.

One important point : if pulp & paper as well as timber industries are dominated by private companies, until today 40% of Indonesia’s oil palm plantations are owned by smallholders (defined by Indonesian law as plantation under 25 hectares).

Summary : On top of logging, oil palm plantations grew enormously and required land that was most of the time taken on forest.

From 1980s, the plague of the forest fires

We have just seen that a key economic policy of the Suharto regime was the aggressive and environmentaly destructive exploitation of forest and its conversion to various crop plantations.

In addition to the direct damages, a devastating side effects is going to add up to the disaster : massive forest fires.

How rainforest had become a fire-prone ecosystem through logging and peatland drainage

Tropical forest (that covered most of Indonesia at the onset of the 20th century) is also referred to as “rainforest”. Except under a severe and long period of drought, this not a fire-prone environment.

This doesn’t mean that fires could not occur naturally, as the analysis of charcoal deposits has shown.

Scientists have found proof of natural fires occurring in Borneo or Sumatra thousands of years ago. But the fact that both islands were still covered by forests a few decades ago suggest that the scale of those ancient fires were lower than today.

Then 1982 came in East Kalimantan. No one had ever seen anything like that. It was an El-Nino year, which induces a very strong dry season in this part of Indonesia.

East Kalimantan province had experienced one of the most severe boom in logging in the 1970s. As elsewhere in Indonesia, 10 years of uncontrolled logging had left large portions of concessions highly degraded (with plenty of dead trees as well as scrubs).

The fires started in June 1982 and were extinguished only with the return of the rain in May 1983. It is estimated that 3,2Mio ha of land (including 2,7Mio of rainforest, of which half of Kutai National Park) were engulfed by the fires.

It was latter established that the degree of damage was directly correlated with the level of forest degradation (Schindler 1989) : undisturbed primary forest quickly recovered by 1988 while logged forest suffered much more severe damages.

Unfortunately things will keep getting worse from this point. In the 1990s, plantation developers had expanded tremendously, first in lowland forest (the most accessible). Later, when this kind of land would became scarcer, they shifted their focus to peatlands.

Peatland refers to a kind of swampy soil, which is usually covered by pristine forest in Indonesia. Once drained and dried out, it’s possible to plant regular crops on it. The issue is that the once-immerged peat is able to keep burning for months beneath the surface if inflamated.

Fire as a land clearing tool

Pulp and paper as well as palm oil plantations require fully cleared land. After more than a decade of wild logging, degraded forest lands and scrubs were abundant but they required a last clearing before planting. Turns out that fire is the most cost-effective way to clear the land, about half as expensive as using mechanical means.

From the 1990s, plantations owners as well as small scale farmers systematically took advantage of the dry season to clear land by fire.

But fire often became uncontrollable, especially during dry El-Nino years. They were escaping to adjacent logged forests which were now fire-prone and also reached drained peat swamps which burned for months.

Data compiled by Global Forest Watch (source) shows that since 2001, nearly half of the fire occured in provinces with heavy plantation-industry, namely Riau, South Sumatra and Central Kalimantan.

40 years of forest fires

From 1982, massive forests fires have become business as usual in Indonesia :

- In 1991, 0,5Mio hectares burned in East Kalimantan.

- In 1994, BAPPENAS (Badan Perencanaan Pembangunan Nasional, the National Development Planning Agency) estimated that 5Mio hectares burned.

- In 1997-1998, fires destroyed an estimated 10Mio hectares according to BAPPENAS reports (half of which was natural forest, Kalimantan was the most affected with 6,5Mio ha burned, then Sumatra with 1,8Mio ha and Papua with 1Mio ha).

- 2006, 2007 and 2012 also had a large haze episode.

- In 2015, about 2,6Mio ha of land burned during the summer.

Those figures include of course land cleared on purpose but also by accident. While some is regenerating as scrubby forests, a significant portion will also be invested by small-scale farmers.

Aside big business, small-scale deforestation by independent farmers

So we have established that the successive unsustainable practices of the logging, wood-processing and plantation industries with the support of a corrupt regime had a terrible effect on the Indonesian forests.

In the meantime, the explosion of the Indonesian population (from 60Mio in 1930 to more than 250Mio today) had of course its own impact on the demand for arable land.

Three factors must be taken into account :

- The traditional “shifting cultivators” which have used slash and burn for centuries. General population growth logically led to an expansion of their cultivated land.

- Transmigrants who opened new agricultural land

- Spontaneous migrants or “forest pioneers” also clearing forest to establish permanent agricultural settlements.

By 1991, it was estimated that each categories contributed respectively to 22%, 13% and 29% of deforestation (Dick 1991 quoted in Sunderlin 1997). But keep in mind that in 1991, we were still in the early phases of plantation expansion. Logging concessions, including the bad ones, don’t technically clear forest : they damage it but it’s still standing.

Transmigration was a government program to sponsor the relocation of families from overpopulated Java, Madura and Bali to the Outer Islands (in 1982, population density was 6 person/km2 in East Kalimantan, 25 in Riau and 760 in Central Java).

The government would allocate each household a parcel of land to farm (usually 2ha), most of the time forested, with the instruction to convert and plant it. About 8Mio of people have been transported between 1969 and 1993.

From 1980s, the transmigration program focused on providing labor for oil palm and timber plantations. In the case of palm oil, households received a smallholdings of plantations and were associated with private (or public) oil firms who provided the access to a processing mills. Such smallholdings are reffered to as plasma and the mill owner as inti.

Many people also migrated independently of the official program. They were often from rural area where land was becoming too scarce for a growing population. They established themselves on the edge of forests and developped cash crop agriculture.

Indonesia is the world second producer of rubber (behind Thailand), third for cocoa (behind Ivory Coast and Ghana) and fourth for coffee (behind Brazil, Vietnam and Colombia). Indonesia is also the largest producer of cloves, cinnamon, coconuts and second for pepper.

The great majority of cash crops are grown by small-scale farmers (80% of rubber plantations in 1997, Kartodihardio and Supriono 2000).

Yet smallholders generally do not clear primary forest because they lack the heavy equipment. They tend to invest secondary forest, degraded lands or plantations abandoned by conglomerates.

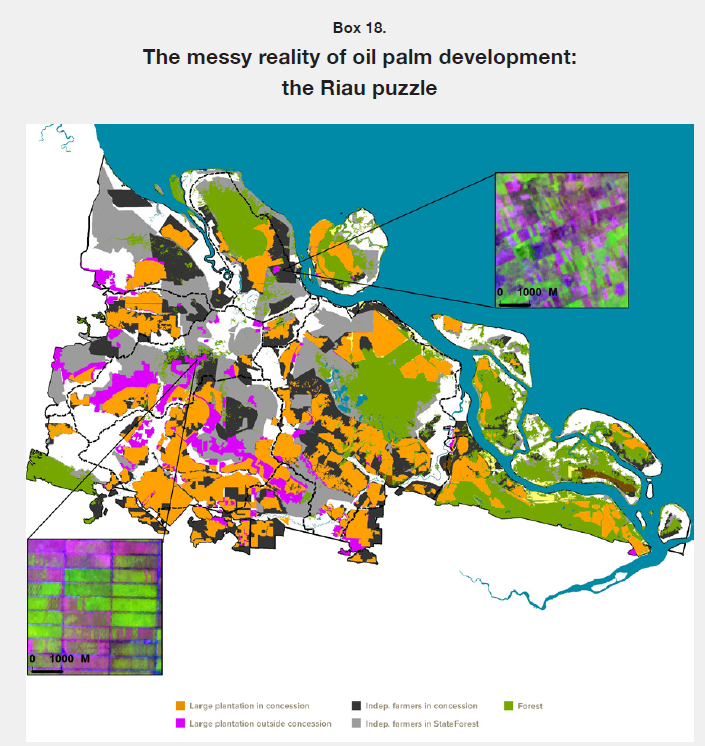

Overall this has created a very messy situation, let’s look for instance at this map in one area of Riau, Sumatra :

From 1998 : post-Suharto Indonesia

The side effects of the Reformasi

After 33 years of reign, Suharto is forced to step down from power in 1998 in the wake of the Asian Crisis of 1997 (the Indonesian Rupiah to US dollar exchange rate plumeted from 2’400 in July 1997 to 14’000 in May 1998) and the pressure of student movements.

Indonesia experiences a period of deep political shake-up which has been solved by far-reaching decentralization reforms. I won’t discuss it in details but one of the direct consequences was that now the ultimate power to grant concession and plantation licences was delegated to the regency level (Kabupaten).

Many regents (Bupati) will soon prove themselves very enthusiastic to support the expansion of plantations on their lands. This was advocated as an efficient way to lift populations from poverty and develop infrastructure in remote areas. Behind the scene, corrupted license trade became the primary tool to fund extraordinary expensive electoral campaigns as well as personal enrichment.

In 2018, a group of journalist under the banner “The Gecko Project” published a string of outstanding investigative journalism work exploring this topic. I strongly advise anyone to go read at least their piece “The Palm Oil Fiefdom” which tells how the regent of Seruyan district literally sold most of the region piece by piece to conglomerates. An essential yet depressing read.

The Central Kalimantan province is a telling example of the typical political games of post-Suharto Indonesia. In 2016 governor election, 2 out of 3 candidates were former timber business man turned district heads who extracted a rent from granting concession licenses. The 3rd one (who won) was none other than the nephew of Abdul Rasyid : a local timber and oil palm baron who is notorious for having ransacked Tanjung Puting National Park for years.

Despite the fall of Suharto, corruption has mutated but is still very strong and pervasive in Indonesia forest management

The stagnation of the original timber industry

Late 1998 is the peak of the logging industry. From this date many concessions have been withdrawn because of violations committed by concession holders. The value of the timber stands in many concession was also declining, most of the valuable and accessible wood having been cut already.

In July 2000, the Ministry of Forestry published an analysis on the status of the logging concessions. Out of 652 existing concessions, 293 were operating with a valid license, 288 had an expired license and 71 had been formally returned to government control.

In 2016, logging concessions are still covering 19Mio ha (BPS) (versus 69Mio ha in 1998). Unfortunately, the reason behind this decrease is that many former concessions has been converted to an industrial plantation of oil palm or pulpwood.

Traditional wood-processing activities (such as plywood and sawnwood) have also stagnated in the last 15 years. They suffered from the shrinking of cheap supply of timber from natural forests, outdated technology and uncompetitive pricing :

- Production of sawnwood dropped from 2Mio m3 in 2005 to 0,8Mio m3 in 2010

- Production of plywood dropped even further from 9,6Mio m3 in 1995 to 3,4Mio m3 in 2010.

Yet according to the International Tropical Timber Organization (ITTO), in 2016 Indonesia is still :

- The uncontested global leading producer of tropical wood.

- The 4th producer of tropical plywood (behind Vietnam, India and Malaysia)

- The 3rd producer of tropical veneer (behind Vietnam and China)

- The 3rd producer of tropical plywood (behind China and Malaysia)

The rise of palm oil and pulp & paper as leading national industries

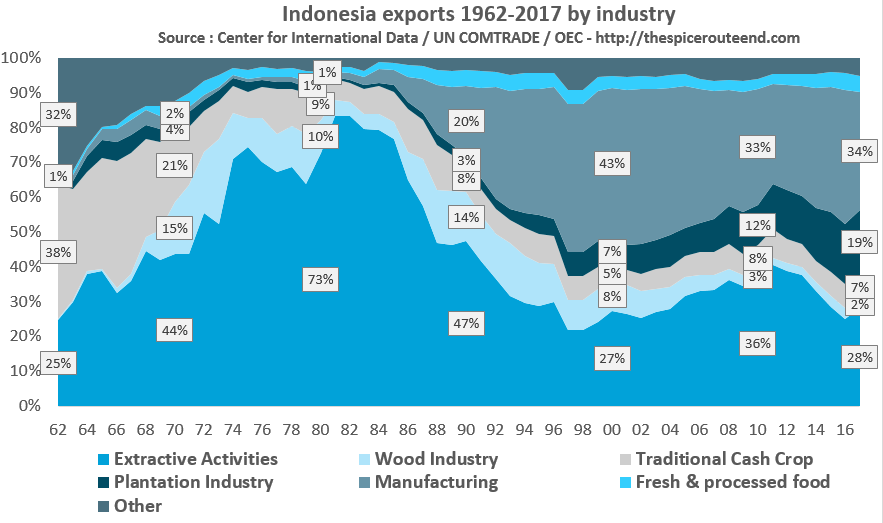

The following charts shows the importance of main industries in Indonesian exports over time. Extractive industries refer to oil & gas and mining, plantation industry to palm oil and pulp and paper. Nowadays, those 2 commodities are only second to coal in Indonesian exports :

Oil palm experienced the most impressive growth. According to the Indonesia Association of Palm Oil Producer (GAPKI), palm oil concessions have expanded from 3’000km2 in 1980 to 116’000km2 in 2016.

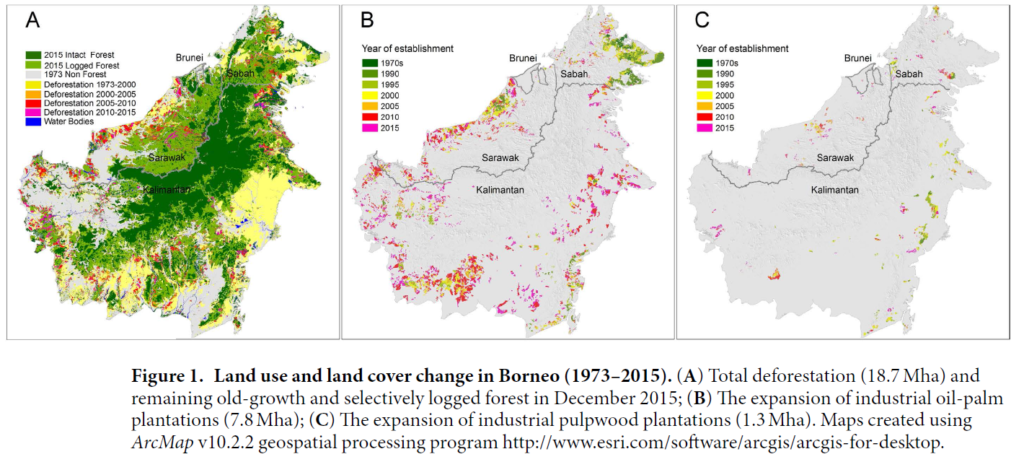

The impact of palm oil on deforestation is debated among scientists. From 1973 to 2015 a study using satellite imagery estimated that only 15% of palm oil plantation in Kalimantan has been established less than 5 years after the land clearing, in contrast with Malaysian Borneo where the figure is 60% (Gaveau & al 2016). This suggests that historically, oil palm development have had a limited impact on forest cover loss.

Nonetheless, from from mid-2000s, oil palm has become the primary driver of deforestation in Kalimantan (Gaveau & al 2016).

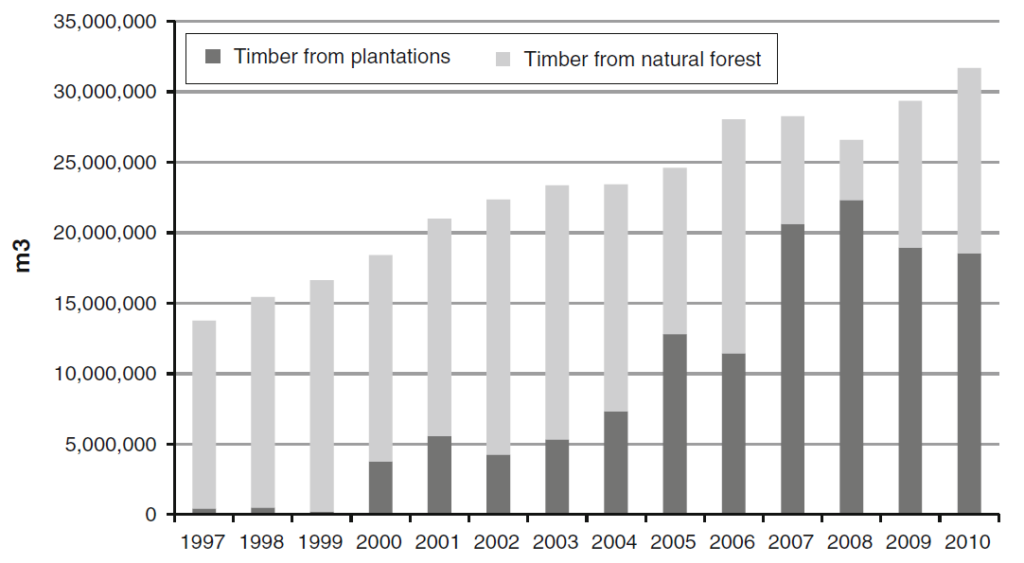

The pulp & paper industry has more than compensated the stagnation of the traditional wood-processing industries. From 1998 to 2010 (Obidzinski & Dermawan 2012) :

- Pulp production capacity rose from 0,6Mio to 7,9Mio metric tons/year while the actual production grew from 0,4Mio to 7Mio tons/year.

- Paper industry processing capacity rose from 1,2Mio to 12,2Mio tons/year while the actual production grew from 0,9Mio to 10,5Mio tons/year.

Pulp & paper industry is centered in the province of Riau in Sumatra and is dominated by 2 multinationals owned by a conglomerate : Asia Pulp & Paper (APP, Sinarmas – Salim family) and Asia Pacific Resources International (APRIL, Raja Garuda Mas Group).

The enormous lack of timber producted in plantations is still an unsolved issue, even though progresses must be acknowledged. In 2010, key pulp and paper producers in Riau still sourced more than half of their raw materials from the conversion of natural forests (Obidzinski & Dermawan 2012).

By 2010 at least 10Mio of hectares had been allocated for HTI development and only half of it had been planted (Obidzinski & Dermawan 2012, 2nd study).

In 2013, timber harvest from plantation was still below 20Mio m3 (FWI 2013). In 2018, timber plantation are still underproductive and unable to fully supply for the industry demand.

Despite the establishment of the timber legality assurance system (System Verifikasi Legalitas Kayu or SVLK) in 2009 and some crackdown on National Park abuses, illegal logging is still a reality in Indonesia. This industry is moving towards Papua, where the stock of precious timber is still plentyful.

In August 2018, a cargo ship was raided in the harbor of Jayapura (Papua province). The investigators from the Ministry of Environment and Forestry found 81 containers of wood highly suspected of being covered by forged documents. Most of the companies behind those containers were part of the SVLK scheme.

A few maps

The first maps illustrate the deforestation process in Borneo from 1973 to 2015, in particular :

- The disastrous effect of logging and forest fires in East Kalimantan.

- The huge expansion of oil palm estates in Central Kalimantan. West Kalimantan is currently following the same path.

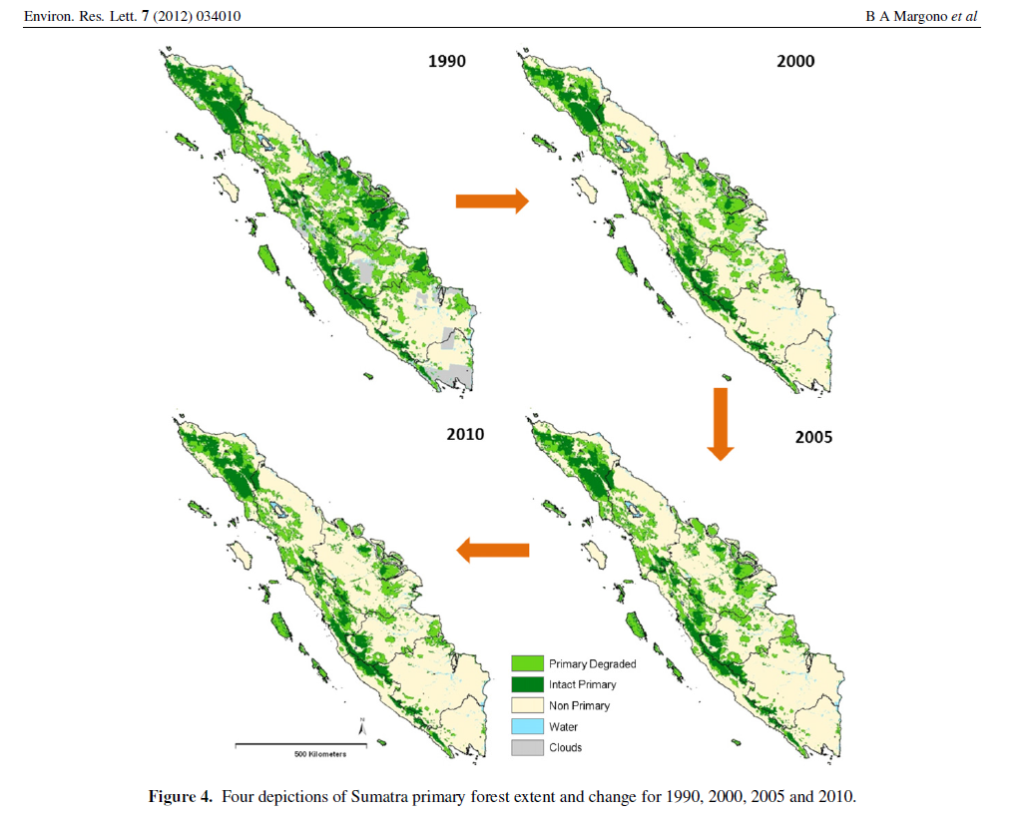

I tried to find similar data for Sumatra. Again it illustrates the massive clearing of forests in Riau, Jambi and South Sumatra provinces.

I found average deforestation rates in Forest Watch Indonesia 2018 report :

- 0,3Mio ha/year in the 1970s

- 1Mio ha/year in the 1990s

- 2Mio ha/year in 1996-2000 period

- 1,5Mio ha/year from 2001 to 2010.

- 1,1Mio ha/year from 2009 to 2013.

Part 3 – analysis : What did Indonesia won from that ?

Forest products and plantation are essentials for the Indonesian economy

The past and current economic contributions of timber-related and plantation industries is undebatable. Through the exploitation of oil & gas, mineral and timber resources, Suharto jump started the economy and rose the income per capita from $50 in 1967 to $980 in 1995. Poverty rates plummeted from 60% to 15% of the population.

In a recent interview, vice president Jusuf Kalla claimed that the palm oil sector alone provides jobs for 5,5Mio people directly and another 21Mio people indirectly (Jakarta Post).

Estimates for the pulp & paper sector are around an additional 2.1Mio jobs (Obindzinsky 2012).

In a context of declining oil & gas reserves in Indonesia, palm oil and pulp & paper exports are crucial to maintain the value of the Indonesian Rupiah against the dollar.

The advent of tycoons

Logging, wood-processing and plantations industries were also instrumental in the rise of the conglomerates than have come to dominate the Indonesian economy.

If we have a look on Forbes’ Indonesia Richest, at least 10 names out of the 50 in the list made a significant share of their fortune in timber or plantation business. In particular :

- Eka Tjipta Widjaja (passed away in Jan 19, No.3) : owner of Sinarmas group which controls Asia Pulp & Paper (APP), Indonesia largest pulp & paper producer as well as Golden Agri-Ressources a major oil palm company.

- Anthony Salim (No.5) : a major actor of the palm oil plantation sector through the Salim group.

- Prajogo Pangestu (No. 10) : owns Barito Pacific which was the largest timber group until 2007 when the family divested completely from the timber business to focus on integrated chemicals.

- Martua Sitorus (No. 15) : co-founder of Wilmar International, the largest global palm oil trader with significant numbers of owned plantations too.

- Bachtiar Karim (No. 21) : owner of the Musim Mas group, one of the largest palm oil producer in Indonesia.

- Sukanto Tanoto (No. 25) : owner of the Royal Eagle Group who owns Asia Pacific Resources International Holding (APRIL), Indonesia’s second pulp & paper producer.

- Ciliandra Fangiono (No. 28) : owner of First Resources, major oil palm producer.

Given that most prominent Indonesian businessmen control their own conglomerate with stakes in hundreds of business, virtually each of them have some interests in plantation companies.

No other business is as well represented as plantations in Forbes’ list.

It is quite clear that the Indonesian business elite have benefited a lot from forest-related activites. Many of them have leveraged their initial investment to diversify their operations to various economic sectors.

What about the people ?

The impact on traditional communities way of life

If forest exploitation brought huge profits to the Indonesian economy and the business and political elite, costs were mostly borne by local forest-edge communities. Centuries-old customary rights sytems over forests were suppressed and it was forbidden for the local population to exploit forest resources falling within concession, even if the forest had provided for their community since generations !

The conversion of forest to plantation had far-reaching consequences on the lives of forest-edge communities. For instance in Kalimantan, indigenous communities of the interior (regrouped under the umbrella name Dayak) traditionely lived off swidden agriculture and the trade of durable forest products (like rattan, honey or tree barks) and would rely heavily on the rivers for water and fish as well as the forests for wild vegetables, fruits and game.

Reckless logging caused massive erosion, increasing the frequency and the severity of floods as well as catastrophic forest fires. The later expansion of plantation (oil palm in particular) and mining further degraded the situation : virtually any single large river in Indonesia is now heavily polluted by fertilizers and chemicals. Villagers must dig well to access drinking water and fishstock has become less abundant.

Research on sample communities have tried to value these economic costs. For the Anak Dalam community (also called orang rimba) of Jambi it is estimated that 55% of the people’s monthly expenditure goes towards things they would previously obtain for free from their forest (like water or fruit). For the villagers of Trimulya in Central Kalimantan, the result is even higher with 61% (Yando Zakaria 2017).

Widespread and brutal social conflicts over land

New Order’s forest policy was centralized and predatory. Traditional dispute resolution mechanisms were suppressed, and local protests were usually dealt violently by police or military personnel “rented” to logging firms. Justice was simply taking its order from the government.

The land acquisition phase for plantation development has always been very problematic, and even despite the fall of Suharto the following pattern remains mostly true until today.

Only a minority of farmers own proper land titles, even for land they have used for generation to grow crops or collect forest products. Companies with the right connections to the local government are often able to obtain permits overlapping with their customary land.

When the rural communities are compensated, it is also very common to only partially fulfill the promises made. In “socialization” meetings (from the Indonesian word socialisasi that refers to public reunion during which projects or reforms are explained to the population) company would promise to build roads, clean water facilities, schools, clinics, meeting hall… The villagers who accept to contribute their traditional land to the plantation would be awarded smallholding plot…

An example of declaration to villagers “You could earn enough money from one poil palm tree to buy a cow, by owning two oil palm trees you could send your children to university, so why don’t you transfer the ownership of your land to company for oil palm plantation project ?” (Colchester et al 2006).

Deceived local communities have sometimes resorted to violence (destroying company equipment, blocking access and occupying building) to voice their protest. This was especially true right after the fall of Suharto.

For instance in August 1998 in the South Tapanuli district of North Sumatra. Villagers of Ujung Gading Jae clashed with PT Torganda who had been allocated a concession on their customary land and burnt a bulldozer. Unidentified men later burnt down 100 houses in 3 villages supposedly in retaliation.

In December 1998 in East Kalimantan, villagers set fire to a basecamp of PT London Sumatra, demanding compensation for their land and the damages to their traditional burial sites. They occupied the camp until May 1999 when armed forced ejected them. 2 people died and 4 other disappeared.

Violence is found on both sides. In 1998, villagers shut down by protest a pulp mill near Porsea, south of Lake Toba. In March 1999, police used force to lift the blockade. Villagers reacted by kidnapping 4 employees of the company, 3 of them died.

According to the Agrarian Reform Consortium (Konsortium Pembaruan Agraria or KPA), there were 659 documented agraria conflict cases in 2017 related to about 0,5Mio ha of land and involving about 650’000 families. Another 278 had been reported for the first half of 2018. For an example of modern land conflict you can read this article for instance.

Systematic labor abuses in plantations

Palm oil plantations do provide employment for the locals. But the industry is infamous for its bad practices that have been repeatedly condemned by NGOs (see two reports from Rainforest Action Network or Amnesty International).

Plantations make a massive use of casual workers and temporary contracts ; very often paid under the regional minimum wages. Employee are often not provided with basic protection equipment while they manipulate hazardous chemicals on a daily basis.

The kernet system is very common. To meet unrealistic production quota (often measured in weight of daily harvested fruits for men and liters of fertilizers spread for women), employee have no choice but to bring an undeclared worker with them (usually the wife, the child or a relative). The kernet as it is called, get a share of his wage, usually 20-35’000Rp a day.

The vulnerability of smallholders

40% of palm oil plantations in Indonesia are owned by smallholders. Yet their average yield is up to 10 times lower than the industrial plantation standard.

Moreover, oil palm fruit bunches must be processed within 48 hours upon harvest in order to be transformed into marketable oil. Hence smallholders are dependent on palm oil mills operators, which is usually a large company given the required investment, that can set the price they want.

For these reasons smallholders are often not really better off after switching to oil palm cultivation. Yet they are stuck with it for at least a decade given that a palm tree is profitable only 6 years after planting.

Part 4 : the future : current trends and policies

It is clear that nowadays, most of deforestation is related to concession management. In its last report Forest Watch Indonesia found that 72% of deforestation in surveyed province happened within concessions.

Unfortunately concessions are here to stay. There is a solid macro-trend behind both paper and palm oil producers. According to the FAO, consumption of vegetable oil will reach 16 kg/person/year in 2050 (12 in 2007). FAO also expect the production of paper and paperboard to reach 700Mio tons/year in 2030 (400Mio in 2010) (Obindzinsky 2012).

Current trends for deforestation

World Resource Institute has set up an absolutely amazing online tool : Global Forest Watch.

It’s possible to display on a map the forest cover loss since 2001, protected areas, land allocated for fiber, logging and oil palm concessions. It’s very powerful and great to visualize things.

Oil palm keeps expanding especially in West and Central Kalimantan provinces. 50% of all deforestation on the island of Borneo between 2005 and 2015 was driven by oil palm development. Annual forest loss trended upward since 2000 and reached its peak in 2016 (Gaveau 18). In the meantime, industrial plantation expansion has been declining since 2012 reaching its lowest level since 2003 in 2017.

On Sumatra, wood fiber and oil palm have already eaten up almost all the forests along the west coast (from Riau to Lampung provinces). Most of the remaining forest is now under a protection status but encroachments are numerous, especially in the very last patches of lowland forests. 2 different hydroelectrical dam projects could have a severe impact in North Sumatra.

Recent reports have highlighted the trend for a shift toward East with oil palm plantation being developped in Sulawesi and logging concessions covering large parts of Maluku islands as well as Papua. Forest Watch Indonesia found evidence of classical forest degradation in those concessions (FWI 2018).

According the the Ministry of Environment and Forestry Ministry, deforestation has decreased by 42% in 2016 and another 24% in 2017 compared to the previous year (Mongabay). Yet WRI’s own analysis gives a different result in 2016. Both seems to agree that the last year trend goes downward.

But 2017 was a non-El nino year, implying less risk for forest fire. 2018 data are not yet available but 2019 might see the return of El-Nino (source), which will put Indonesia’s apparent recent success to a real test.

Progresses on the government’s side

Yet it seems that things are slowly changing in Indonesia as it is illustrated by the merging in October 2014 of the Ministry of Forests with the Ministry of Environment.

However one must never forget that the Indonesian government has a difficult equation to solve : preserve the environment while providing badly needed jobs and foreign exchange revenue to the country.

Hence the current policy revolving around 2 main axis :

- Stop the territorial expansion of the plantations (both pulpwood and palm oil) by increasing yields and converting in priority degraded lands

- Fight forest fires, especially through the moratorium on the conversion of peat.

The government has nevertheless ambitious plans for the wood-processing industry and pulp & paper in particular. According to its National Forestry Master Plan published in 2011, its contribution to GDP is expected to increase by 300%. Accordingly, industrial timber plantations are planned to reach 14,7Mio ha (3 times the surface allocated in 2010) that should produce 362,5Mio m3/year (19 times the production in 2010…) (Obindzinski 2012).

Reducing pressure on land by increasing yield

Nowadays, industrial large-scale oil palm producers are able to able to produce about 4 tons of oil per hectare. Smallholders usually produces between 0,2 and 2 tons/ha.

The Indonesian government expect smallholders to boost their productivity through better-quality seeds, standard compliant fertilizers and training to best farming practices.

But this is not something that can be done instantly. An oil palm plantation is a 25 years venture that is not immediately profitable. Seedlings become fruit-bearing trees after 3 years and reach their peak productivity 10 years after planting. Cutting down young trees even to replace them would be financially disastrous for farmers.

In 2017, the government launched a replanting program that allocates free seedlings to smallholders with aging trees as well as help to obtain land title certificates.

In parralel, officials also plan to impose Indonesia own sustainability standard for palm oil (ISPO) on all operators (including smallholders) by 2020. Compared to other existing certifications like the RSPO, it is considered weaker (source) but it should still bring improvements.

The issue is that smallholders are far from ready and the government cannot decently criminalize millions of poor farmers. Preliminary studies have shown that at best, half of farmers could be certified. To begin with, few of them are able to show a land title (which is a simple plantation registration certificate known as STD-B for smallholders), so there is no official limits to their land and it is impossible to make sure it’s not encroaching on forest for instance. 89% of smallholders surveyed also used lower cost and non compliant seedlings and fertilizers (Institut Pertanian Bogor 2018).

Widodo is pushing hard for its agrarian reform to progress (which cornerstone is to issue official land titles to all farmers) but the amount of work involved is also huge.

Meanwhile, top oil palm producers are also developping new augmented species that are supposed to produce up to 10 tons / ha (IUCN 18).

So on paper it seems possible to increase the production without encroaching on remaining forests.

But scientists have already warned not to expect a miracle. Improved yields would make palm oil even more competitive on the global market and might simply force other oil crops out of the market.

Improved yields will only have a positive impact on biodiversity if the governments Indonesia is able change the industry paradigm that has so far operated with minimal consideration for the environment.

Managing Indonesia economy’s exposure to palm oil

There is also growing concerns that Indonesia’s agriculture sector is overexposed to a drop in global oil palm prices. The plan of the government is to absord any peak in production through local consumption of biodiesel.

Through Perpres No. 66/2018 the government has made mandatory the use of 20% blended biodiesel (which is mostly used by trucks as well as heavy and military equipments). Coordinating Minister Darmin Nasution has declared : “for palm oil, our policy is to boost demand. We cannot stop production of palm oil because the plant are already in production. That is why we are creating demand for palm oil products” (Jakarta Post).

In December 2018, the government also announced that it will stop collect export levies from palm oil exporters when price are below $570/ton and only collect a reduced amount until prices reach a given threshold. This policy is supposed to help producers to be more competitive on global markets and help them withstand low price periods.

Are moratorium effective ?

In 2011, Yudhoyono’s government issued a Presidential Instruction (Inpres) imposing a 2 years moratorium on issuing new permits for exploitation of conversion of primary forest and peatland. The area concerned was covered by the Moratorium Indicative Map (MIM) which covered between 64 and 72Mio ha of land. Permits issued prior to the Inpres were not affected by it.

Despite being extended during 6 years (via Inpres No.6/2013 and Inpres No.8/2015), the moratorium failed to stop deforestation : 831,053ha of forest were lost within the protected area from 2011 to 2017. During 2015 fires, 31% of the fire hotspots were detected inside it too (Greenpeace 2017).

The regulation shortcomings are now clear :

- The policy did not protect secondary forests but mostly focused on areas that are already off-limit like conservation areas or protection forests.

- It accepted a lots of exceptions : permits approved “in principle”; infrastructure projects, extension of existing permits …

- There were some backroom deals : the Moratorium Indicative Map was never publicly released and repeatedly revised without open consultation

In the reaction to the disastrous 2015 fire season, president Widodo reinforced in December 2016 the 2014 instructions given on peatland clearing and draining (Perpres No.57/2016). Peatland deeper than 3m is now off limit for concessions and 30% of peat dome must be preserved (NGOs have lambasted this point, arguing that it’s not possible to drain 70% of a dome without affecting the other 30%, see Mongabay 2016).

Then in 2017, it was defined that half of the country’s 24Mio ha of wetland would have to be conserved, and restored if already part of an exploited concession. Plantation moguls contested this decision in court but so far Adminstrative Court has supported the government plan (Mongabay). For the first time, an environmentally-restrictive regulation is applying to existing concessions.

In parallel, the Peatland Restoration Agency have been created and tasked to coordinate the restoration of 2,4Mioha of peatland in Indonesia.

Even if 2017 was not an El-Nino year, the primary forest loss in protected peat areas has been reduced by 88% compared to 2016 (WRII 2018).

In September 2018, president Widodo went even further by issued an new Presidential Instruction commanding all level of governments to halt all new permits issuance (including those which had already obtained preliminary permits) and increase the productivity of existing palm oil plantations. From what I understand, this new moratorium accepts no exception. I haven’t been able to find any analysis on its effect, but it’s probably a bit too early for that.

The long awaited unified land-use map

One of the reason of the mismanagement in Indonesian forestry has been the lack of accurate maps of Indonesian forests and concessions. For decades, the Indonesian government has managed its forests based on statistics that had serious shortcomings. For instance in 1997 the land officialy defined as under Permanent Forest Status was 114Mio ha while the estimation of actually forested land was 98Mio ha (FWI 2002).

One of Suharto’s closest crony (Mohammed “Bob” Hasan) was convicted in 2001 for having corruptly siphoned off around $243Mio allocated for the forest mapping effort (source).

Government has long claimed that timber and tree crops plantation could be developped because according to its data, there were still land available.

In December 2018, the government through the National Geospatial Agency (Badan Informasi Geospasial or BIG) has finally achieved and published the first ever unified map of land-use in Indonesia.

This biblical task was initiated in 2011, and required the synchronizing of 85 existing and disparate map, maintained by 19 government agencies.

This should be a crucial tools in reducing the number of conflicts over land use as well as the common overlapping of concessions over protected forests.

Yet and despite a ruling of the Supreme Court, the government still refuses to date to fully release the data online, arguing that it must control who has accessed to sensible information especially concessions of mines or oil palm.

Disappointing palm oil industry internal efforts

On the producer’s side

In 2004, the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) is funded under the initiative of the palm oil industry. Legally, it’s an NGO based in Switzerland.

Its goal is to use market mechanism to reform the way palm oil is produced and used. The main activity of the RSPO is to define and maintain a quality standards for “Sustainable Palm Oil” (SPO) and to encourage its trade to the exclusion of “dirtier” palm oil.

Yet it’s only in 2018 that the RSPO has adopted new standards prohibiting the clearing of any type of forest (previously clearing of secondary forests and peat below 3m-depth was accepted).

From 2013, virtually all the major players of the agribusiness industry have issued a “Non Deforestation, Peat, Exploitation” (NDPE) policies under the pressure of civil society groups.

In the most recent years, it has become quite clear that large plantation conglomerates (both pulp & paper and palm oil) has been very hypocrital in their “no deforestation” commitments.

Most of them has been caught using opaque corporate structure (usually assets owned through a cascade of shareholding with nominees at several level, potentially in offshore juridictions) to dissimulate their control on plantation operating in violation of their sustainability commitments (see for instance Associated Press 2018).

This kind of corporate structure is also very likely to hide from the public the involvement of politicians, army and police officers in the palm oil expansions.

When proven guilty by NGOs, companies would publicly divest from their rogue operations but keep it under control behind the scene.

According to a recent analysis, RSPO certifications generated slightly positive outcome in terms of yield and market price. But it had no significant impact on the access of the population to healthcare, on the decline of orangutan population or the number of fire outbreak (Morgans 18).

On the consumer’s side

In September 2018, Greenpace pointed out that 12 of the world’s largest brands (namely Colgate-Palmolive, General Mills, Hershey, Kellog’s, Kraft Heinz, L’Oréal, Mars, Mondelez, Nestlé, PespiCo, Rcikitt Benckiser and Unilever) were still sourcing from at least 20 palm oil producers and traders that actively cleared rainforest.

So far large multinational have not proactively monitored their supply chains thoroughly. They tend to wait for NGOs to identify deforestation cases implying suppliers and then treat it as an isolated case.

They have mostly outsourced much of this responsability to sustainability consultants (like TFT) and their direct suppliers (palm oil traders like Wilmar, Musim Mas, Golden Agri-Resources…). The progress of the sustainability politics are measured by the share of suppliers having published an NDPE policies, and that’s it, no further audit. Producers that are not involved into a case brought by NGO are presumed compliant even though there are plenty of evidence that it’s utterly wrong.

In September 2018, Nestlé announced that it would starting monitoring its supply chain using satellite imagery. It tooks 8 years for the multinational to came to this measure, while it has published an NDPE pledge in 2010.

Today Greenpace is focusing its campaigning efforts on the largest oil palm trader Wilmar (an Indonesian controlled company based in Singapore and implied in 40% of the world volume). Because they control crucial assets for exports especially in Indonesian ports, they are a real bottleneck for the whole industry.

Greenpeace is pushing for Wilmar to force every single of its suppliers to publish their mills’ location data and their concession maps and to cut off any business ties with non-compliant companies. Then the supply chain must be independently certified as sustainable by 2020. In January 2019, Wilmar announced that it would start to freeze purchases from non-compliant suppliers (Mongabay Jan 19).

Towards an actual environmental justice ?

The fall of Suharto opened the door for finally bringing to court companies damaging the environment and the corrupted officials they worked with.

Cases are brought to court generally either by the Comission for the Eradication of Corruption (Komisi Pemberantasan Korupsi or KPK), established in 2002 or the Ministry of Environment (KLHK). Both have won some very high profile cases already.

Martias Fangiono (owner of First Resource Ltd., one of Indonesian largest agribusiness company) was convicted in 2007 to 1 year and half in jail and to pay 346bn Rp (about $35Mio) for corrupting the then governor of East Kalimantan province (Suwarna Abdul Fatah, also convicted) to get forest convertion licences issued. His firm cut almost 700,000 m3 of timber in the concerned area.

This is unfortunately more the exception than the rule. The KPK is wary in prosecuting cases. The agency sticks to a strict strategy to maintain a 100% success rate in court, hence only moving forward with the cases which have irrefutable evidences. By law this means catching culprits red-handed accepting or delivering a bribe or demonstrate that his actions resulted in state losses. Corruption in the plantation sector often involves more complex schemes than embezzlement or procurement scams.

I found only a few similar case in the following years : the Bupati of Pelalawan (Riau) Tengku Azmun Jaafar in 2007 (Kompas) and the Bupati of Buol (Central Sulawesi) Amran Batalipu in 2013 (Kompas).

Yet, since 2014, the Ministry seems to have upped its game.

In 2014, former Riau governor Rusli Zainal was convicted to 14 years in jail (reduced in 2017 to 10 years) for accepting various bribes to issue licences (Kompas, Kompas)

In 2015, another Riau governor Annas Maammun was convicted to 6 years in jail for similar reasons (Kompas). In 2018, former head of Kutai Kartanegara district in East Kalimantan was convicted to 10 years in jail for having issued illegally palm oil plantation licence (Tribun Jabar).

In 2016, the Ministry of Environment and Forestry won its final trial in Supreme Court against PT Merbau Pelalawan Lestari, a timber plantation firm accused of illegaly clearing 5’590ha of forest in Sumatra. The company was ordered to pay a staggering 16 trillion IDR (more than $1bn) in fines, the highest penalty ever given in Indonesia for an environmental case.

The previous record has been set in 2015, with the conviction of PT Kallista Alam to 366bn IDR (about $27Mio) in fines for clearing about 1’000ha by fire in the Tripa peat swamp in Aceh province.

But in both cases, fines have not been collected yet despite cases already settled by the highest Indonesian juridiction. The Ministry is still struggling to have the regional courts with authority on the case to exectute the ruling. It will probably be done one day, but there are many ways to slow down (or accelerate) an administrative matter in Indonesia with the proper connections (source).

In 2018, court sentenced former governor of Southeast Sulawesi Nur Alam to 12 years in jail for corruption in the process of nickel-mining licence issuance. KPK brought along an academic who evaluated the environmental, economic damages and rehabilitation costs to 2,7 trillion Rp (about $185Mio). Yet those damages were eventually discounted by judges from their decision.

The multiplication of cases prosecuted and the increasing amount of fines seems to indicate that things are changing slowly. On the other hand, the old way of doing is still efficient : in November 18 an environmental activist known as Budi Pego has been sentenced to 4 years in jail for allegedly having displayed a banner with a hammer and sickle logo during a rally to oppose the exploitation of a gold mine in Tumpang Pitu, East Java. On November 2013, Zulkifi Hasan who was then Forestry Minister and is now speaker of the high chamber of the Indonesian parliament (MPR) issued a decree changing the status of almost 2’000ha of forest from protected to production, allowing mining operations to begin.

What should be done now ?

Solutions to eradicate deforestation along the palm oil supply chains are well identified today. Large global agrobusiness groups as well as palm oil traders must force every single suppliers to disclose the position of their plantation and mills. Any non compliant suppliers must be blacklisted.

Then every actor must prove with satellite imagery that not a single plantation is established or encroaching on existing forest (in the case that not the whole concession land had been converted). Mills capacity must be disclosed too and compared with the surface of the compliant surrounding plantations in order to detect “smuggling” of rogue palm fruits (this is the current strategy of Greenpeace towards Wilmar).

A similar mechanism shall also be promoted for pulp & paper industry (read this article).

On the government side, any projects of establishing or upgrading a pulp or palm oil mills must be assessed and authorized only if the operator can prove he is able to secure a regular supply of raw materials coming from compliant plantations.

It is also adamant that the government finally enforces the forestry law that prevent a logging concession to be converted to a plantion. Conversion licences must be systematically refused in such case and the requesters offered to use available degraded, non-forest land.

Very large parts of Indonesia’s remaining primary forests are still unexploited parts of logging concessions. There are thus at risk of being logged. In the worst case scenario (exploitation reaches 100%) then primary forests would decline from 28% of Borneo (2014) to 12% (Gaveau 2014).

I want to keep myself informed about the recent developments, what should I read ?

- Mongabay is an excellent and rather professional source for environmental news in Indonesia.

- CIFOR in Bogor is one of the global leading research center on forestry, publishing very interesting studies.

- World Resource Institute Indonesia runs a great blog as well as the powerful Global Forest Watch tool.

- Forest Watch Indonesia has a good website too, the Indonesian version is kept more up to date.

Notes

Sources I used to write this article

If you have to read only one thing, go for this awesome-yet-15-years-old report :

- Forest Watch Indonesia / Global Forest Watch. 2000. The State of the Forest: Indonesia. Bogor, Indonesia: Forest Watch, Indonesia and Washington DC: Global Forest Watch (downloadable here)

About deforestation

- The report Global Forest Watch – State of Indonesian Forest (2002) gives us estimates for 1950, 1985 and 1997 forest cover, based on :

- L.W. Hannibal. 1950. Map of Indonesia. Planning Development, Forest Service, Jakarta, in: Forest Policies in Indonesia. The Sustainable Development of Forest Lands. (Jakarta, Indonesia: International Institute for Environment and Development and Government of Indonesia, 1985). Vol 3. Ch 4.

- In 1990, a nationwide mapping exercice was undertaken as part of the transmigration program dubbed Regional Physical Planning Program for Transmigration or RePPProt that gives an estimate of the forest cover in 1985.

- UNEP-WCMC, Tropical Moist Forest and Protected Areas: The Digital Files. Version 1. Cambridge: World Conservation Monitoring Center for International Forestry Research, and Overseas Development Administration of the United Kingdom, 1996.

- Sunderlin & Resosudarmo. 1996. Rates and Causes of Deforestation in Indonesia : Towards a Resolution of the Ambiguities. CIFOR Occasional Paper No. 9 (link)

- MacKinnon J.. 1997. Protected areas systems review of the Indo-Malayan realm. The Asian Bureau for Conservation Limited (link).

- H. Kartodihardjo & A.Supriono. 2000. The Impact of Sectoral Development on Natural Forest Conversion and Degradation: The Case of Timber and Tree Crop Plantations in Indonesia. Bogor, Indonesia: CIFOR. Occasional Paper 26(E) (link).

- C.V. Barber. Forests, fires and confrontation in Indonesia in Richard Matthew, Mark Halle, and Jason Switzer 2002: Conserving the peace: Resources, livelihoods and security, pp. 99-169. IISD/IUCN (link).

- Margono et al. 2012. Mapping and monitoring deforestation and forest degradation in Sumatra (Indonesia) using Landsat time series data sets from 1990 to 2010. Environmental Research Letters 7 (2012) (link).

- Gaveau et al. 2013. Reconciling forest conservation and logging in Indonesian Borneo. PLoS One 8(8):e69887 (link).

- Margono et al. 2014. Primary forest cover loss in Indonesia over 2000-2012. Nature Climate Change, NCLIMATE 2277.

- Abood et al. 2014. Relative contributions of the logging, fiber, oil palm and mining industries to forest loss in Indonesia. Conservation Letters, 2015, 8(1):58-67 (link).

- Gaveau et al. 2016. Rapid conversion and avoided deforestation: examining four decades of industrial plantation expansion in Borneo. Sci. Rep 6, 42017 (link).

- Kementerian Lingkungan Hidup dan Kehutanan, Statistik Lingkungkan Hidup dans Kehutanan Tahun 2017. (link).

- Ministry of Environment and Forestry, The state of Indonesia’s forests 2018. (link).

- Forest Watch Indonesia. 2018. Unstoppable deforestation : portraits of deforestation in North Sumatera, East Kalimantan and North Maluku (link).

- Gaveau et al. 2018. Rise and fall of forest loss and industrial plantations in Borneo (2000-2017). Conservation Letters. 2018;e12622 (link).

On timber, pulp & paper industry

- Barr. CM. 1998. Bob Hasan, the Rise of Apkindo, and the Shifting Dynamics of Control in Indonesia’s Timber Sector. Indonesia No. 65 (Apr., 1998), pp. 1-36 (link).

- EIA/Telapak. 1999. The Final Cut : Illegal logging in Indonesia’s Orangutan Parks (link).

- K. Obidzinsky & A. Dermawan, “New round of pulp and paper expansion in Indonesia: What do we know and what do we need to know ?”, ARD Learning Exchange 2012 (link).

- K. Obidzinsky & A. Dermawan. 2012. Pulp industry and environment in Indonesia: is there a sustainable future ? Environ Change (2012) 12:961-966.

- Telapak. 2013. Illegal logging in Tanjung Puting National Park – An update on The Final Cut Report (link).

- Obidzinski & Kusters. 2015. Formalizing the logging sector in Indonesia: historical dynamics and lessons for current policy initiatives. Society & Natural Resources, 28:5, 530-542 (link).

- H.N. Jong, “Paper giant RAPP bows to peat-protection order after Indonesia court defeat”, December 2017, Mongabay.com (link).

- International Tropical Timber Organization. 2018. Biennial review and assessment of the world timber situation (link).

- INTERPOL Environmental Crime Programme. 2018. Green Carbon, Black Trade – Illegal logging, tax fraud and laundering in the world’s tropical forests (link).

- Anti Forest Mafia Coalition. 2018. APP and APRIL violate zero-deforestation policies with wood purchases from Djarum Group concessions in East Kalimantan (link).

- S. Wright, “Forests watchdog sends ultimatum to Indonesian paper giant”, May 2018, The Seattle Time (link).

- Elisabeth A, “Dokumen palsu kayu-kayu dari hutan Nabire”, August 2018, Mongabay.id (link).

- Riski P., “Penyelundupan 40 kontainer kayu merbau asal papua digagalkan, bukti pebalakan liar marak”, December 2018, Mongabay.id (link).

- Tempo, “Illicit timber laundering machine”, December 2018. Tempo English Edition.

On palm oil industry

- Pin Koh L. & Wilcome DS.. 2008. Is oil palm agriculture really destroying tropical biodiversity ? Conservation Letters 1 (2008) 60-64 (link).

- Pirard R. et al. 2015. Deforestation-free commitments: The challenge of implementation – An application to Indonesia. Working Paper 181, Indonesia: CIFOR (link).

- Nikkei Asian review, “Starts planting high-yielding oil palm, aims to boost output by 15%”, April 2016 (link).

- The Gecko Project, “The Palm Oil Fiefdom”, October 2017, Mongabay.com (link)

- Stephen Wright, “AP Exclusive: Pulp giant tied to companies accused of fires”, December 2017, Associated Press (link).

- Forest Peoples Programme. 2017. A comparison of leading palm oil certification standard (link).

- Aidenvironment. 2018. Palm oil sustainability assessment of Salim-related companies in Borneo peat forests (link).

- Philip Jacobson, “Revealed : Paper giant’s ex-staff say it used their names for secret company in Borneo”, July 2018, Mongabay.com (link).

- Greenpeace International. 2018. The Final Countdown: Now or never to reform the palm oil industry (link).

- The Gecko Project, “The secret deal to destroy paradise”, November 2018, Mongabay.com (link).

- Institut Pertanian Bogor. 2018. The Readiness of Independent Smallholders to fulfil ISPO Certification Principles: Case Study of Three Villages in Indonesia (link).

- Meijaard & al. 2018. Oil palm and biodiversity – A situation analysis by the IUCN Oil Palm Task Force. International Union for Conservation of Nature (link).

- Morgans & al. 2018. Evaluating the effectiveness of palm oil certification in delivering multiple sustainaility objectives. Environmental Research Letters 13 (2018) 064032 (link).

- Mongabay, “Palm oil giant Wilmar promises to take harder line with errant suppliers”, Mongabay.com (link).

About impact on people / politics

- Colchester et al. 2006. Promised land. Palm oil and land acquisition in Indonesia : Implications for local communities and indigenous peoples. Forest Peoples Programme, Perkumpulam Sawit Watch, HuMA, World Agroforestry Centre (link).

- Humanity United. 2012. Exploitive labor practices in the global palm oil industry (link).

- Bizard V. 2013. Rattan futures in Katingan: why do smallholders abandon or keep their gardens in Indonesia’s ‘rattan district’ ? Working Paper 175. Bogor, Indonesia: World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF) Southest Asia Regional Program. 22p (link).

- L.R. Carrasco et al. 2014. A double-edged sword for tropical forests. Science 346, 38 (2014).

- Norwegian Centre for Human Rights. 2015. The Palm Oil Industry and Human Rights: A Case Study of Palm Oil Corporations in Central Kalimantan (link).

- Rainforest Action Network. 2016. The human cost of conflict palm oil (link).

- T. Tombourou, “‘Empty pocket season’: Dayak women farmers grapple with the impacts of oil palm plantations”, August 2018, Mongabay.com (link).

- Rainforest Action Network. 2018. The human cost of conflict palm oil revisited (link).

- Asian NGO Coalition for Agrarian Reform and Rural Development (ANGOC). 2019. In defense of land rights – A monitoring report on land conflicts in six Asian countries (link).

- Amnesty International. 2018. The great palm oil scandal (link).

Yando Zakaria & al. 2017. Konflik tanah dan sumber daya alam dari perspektif masyarakat, Conflict Resolution Unit (link). - H.N. Jong, “Unified land-use map for Indonesia nears launch, but concerns over access remain”, April 2018, Mongabay.com (link).

- H.N. Jong, “Five years after zero-deforestation vow, little sign of progress from Indonesian pulp giant”, April 2018, Mongabay.com (link).

- H.N. Jong, “Indonesia land swap, meant to protect peatlands, risks wider deforestation, NGOs say”, April 2018, Mongabay.com (link).

- H.N. Jong, “When palm oil meets politics, Indonesian farmers pay the price”, June 2018, Mongabay.com (link).

Current trend

- F. Stolle, “Indonesia’s Ambitious Forest Moratorium Moves Forward”, June 2011, World Ressource Institute Indonesia (link).

- Mongabay Haze Beat, “Green groups raise red flags over Jokowi’s widely acclaimed haze law”, December 2016, Mongabay.com (link).

- Greenpeace Indonesia, “Six Years of Moratorium: How Much of Indonesia’s Forests Protected?”, May 2017 (link).

- H.N. Jong, “Land-swap rule among Indonesian President Jokowi’s latest peat reforms”, August 2017, Mongabay.com (link).

- H.N Jong, “These 3 companies owe Indonesia millions of dollars for damaging the environment. Why haven’t they paid?”, August 2017, Mongabay.com (link).

- H.N Jong, “Indonesian graftbusters put a price tag on environmental crime”, March 2018, Mongabay.com (link).

- H.N. Jong, “Indonesia forest assessment casts an optimistic light on a complex issue”, July 2018, Mongabay.com (link).