Who are the Toraja ?

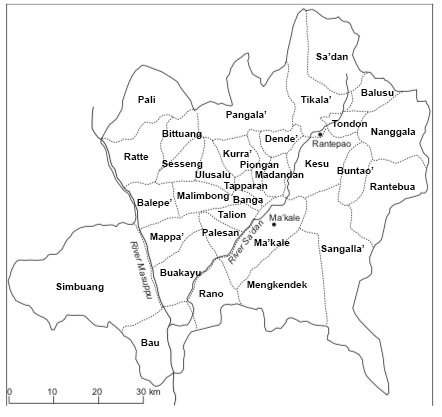

Today, Toraja is the name given to the ethnic group living by the Sa’dan river in the highlands of South Sulawesi around the towns of Rantepao and Makale. This area is commonly called Tana Toraja.

They share a common language (which had originaly no written script) and culture.

Until the arrival of Christian missionaries in 1913, Toraja practiced a form of animism called Aluk To Dolo ‘Way of the Ancestors’ that includes the cult of ancestors, belief in spirits and in local myths about the creation of the earth. As a purely oral culture, many local particularities existed.

“Like other indigenous belief systems of small-scale societies, Toraja religion evolved in intimate relationship to local landscapes. It has been until recently such an integral part of people’s knowledge of their own environment and how to live in it, that it was scarcely separable from other aspects of life. Indeed there was no need to think of it as a separate, or even to give it a name” (Waterson, 2009).

I have dwelled upon Aluk To Dolo and its rituals in another article.

According to Nooy-Palm who quotes Adriania, the name Toraja comes from the Bugi language to-ri-aja ‘the people of the highlands’. It’s worth noting that historically, it encompassed all the people of the Sulawesi highlands, including those living in the current province of Central Sulawesi. In Kruyt’s monography of the people of Central Sulawesi (1925), the Toraja region spans as far as modern day Poso, Tentana and Luwuk.

Hence the use of the name Sa’dan Toraja by ethnographers to describe inhabitants of modern day Tana Toraja.

Tana Toraja

Tana Toraja is described by ethnographers as a collection of neighbouring adat-communities (from the Indonesian word adat ‘custom’), called lembang by the Toraja, which shared a common set of laws and customs.

The Dutch administration roughly sticked to this original division when they defined the administrative districts. Nowadays, kecamatan (district) still adheres more or less to the old lembang (some unification has taken place though). The lembang have united themselves on few occasion in the history (almost always in a context of war with outsiders) but were in general rather independent from each others and had their own leadership.

The lembang of Mengkendek, Sangalla’ and Ma’kale were ruled by a prince (puang) and the nobility was especially strong there. They married extensively with the noble families of the Bugis kingdoms of the South. The three ‘princely’ districts are called the Tallulembangna.

Each lembang could present particularities in a given aspect of the ritual prescription or social organization (a detailed description is available in Nooy-Palm, vol I). A very singular ritual called ma’nene, which has survived until today, is only undertaken in the North near Mt Sesean for instance.

Smaller ritual communities also existed within the lembang. At each level, those communities were mobilized to perform some rituals of the Aluk To Dolo (the indigenous religion). With the Christianization, large parts of this social divisions have fell into disregard :

- The family (siruran).

- The village (tondok), potentially further divided into wards (saroan) a group of neighbours collaborating for agricultural work and related rituals.

- Bua’ or penanian which often coincides with a village tondok (even though some villages include two bua’, and one bua’ can span over several villages). Inhabitants of a bua’ celebrate the bua’ padang ritual (a kind of agricultural New Year celebration) together. This ritual, now gone, included a choral hence the term penanian from nani ‘sing’.

- Patang penanian a federation of 4 bua’ (patang ‘four’) which has its own adat-chief and hold important fertility rituals (like the merok feast or the great bua’ feasts) together.

Economy

The Toraja are still a predominantly rural society. The staple food is rice (supplemented by maize, millet …) cultivated on irrigated land (ind. sawah) and dry fields (ind. ladang). The last type of land is the most common. The main cash crop is coffee.

A majority of the territory of Tana Toraja (about 4/5) is made of woodlands and wastelands with is rather unfertile or poorly suited for cultivation soil. This leads to a dramatic shortage of agricultural land, which has in turn largely participated in the important immigration of Toraja to other regions of Indonesia.

The Toraja are not able to produce all the rice they consume and must import from outside.

Social organization

The tongkonan

The tongkonan is both a physical house and the group of person who claims membership in it. Put it differently, it is a clan which is centered around one house. Most of the tongkonan members are not actually inhabitating it.

A house can’t be moved (because the placenta of many ancestors are buried next to it, even though nowadays many people are unable to say where is their own placenta buried), and must be regularly rebuilt. The barn can be moved, for instance in the case of a divorce.

A child belongs to the clans of its mother and its father. As a consequence, any person may claim to belong to dozens of different houses. Membership to a tongkonan is actually activated only at certain times, principally for rituals to which all members must contribute. Only people of very high ranking (and high wealth) do actually maintain ties with a great number of houses.

Those ties are not curtailed at marriage, so a married couple must contribute equally to the rituals associated to the ancestors of each spouses. At funerals, if the deceased has parents from different districts, it’s the ritual form of the mother’s district that must be respected.

Most tongkonan own indivisible ressources known as mana which can include heirlooms (old swords and krises, precious ornaments, textiles …) bamboo groves, coconut groves and of course ricefields. In the past, it could also include slaves.

It also owns a stone grave (liang). Given people maintain ties with different houses, they must often choose their burial site, which is potentially a source of conflict.

The importance of genealogy

A member of a tongkonan has to know its genealogy, especially the names of the ricefields it owns and the way it was inherited so he can defends against false claims of ownerships.

Members of eminent families used to have a very extensive knowledge of their genealogy, which usually started by a semi-god ancestors (to manurun) who was thought to have descended from heaven.

Nooy-Palm reports that in the 1970s, the youth had already stopped being trained to recite the genealogy of their clan while some elders were still able to detail their genealogy over 24 generations !

The story of the tongkonan, its origin in the Toraja mythology, the accomplishments of the ancestors were recalled in a poetic way in the ritual speech and the chants of the indigenous priests during rituals.

On a greater scale, the tongkonan is a knot in a complex web of relationship called marapuan, translated by ethnologist by ramage. Each marapuan was roughly the lineage descending from a founding ancestors, who had built the first house (which is called tongkonan because of its original status as opposed to banua, the word used for common houses) that have its own name and becomes the social and religious center of all the marapuan.

In the course of the history, the marapuan often branches out which is symbolized by the founding of a new ‘child’ tongkonan who bears its own name but still acknowledge its ties with the ‘mother’ tongkonan (usually one per adat-community). Sub-ramages can be called rapu.

The marapuan and the rapu served essentialy when celebrating the major fertility rituals. Those rituals are sponsored and centered around one tongkonan but the whole marapuan is called upon for contribution.

A stratified society

The Toraja society was organized under a system of 4 ranks :

- The high aristocracy (tana’ bulaan ‘the golden stake’) [maybe 5% of the population]

- The lesser nobility (tana’ bassi ‘the iron stake’) [maybe 10%]

- Commoners (tana’ karurung ‘the sugarpalm stake’)

- Slaves (kaunan or tana kua-kua ‘the reed stake’) [5 to 40% depending on the district]

About the nobility

In the old days, there was a strong taboo on a woman to marry a man of lower rank. The rank of the child would be inherited from the mother. Things have changed today but things like a marriage between a noble woman and a former commoner or even slave are still extremely uncommon.

Hierarchical attitudes were more or less ingrained depending on the region. They were the most pronounced in the southern district of Sangatta, Ma’kale and Mengkendek, the ‘princely’ districts.

The most complex rituals were the prerogative of nobles (and anyway they were the only one who could afford their cost). They were also the only one authorized to carve their house and to build its roof with a saddle-structure.

The aristocracy have dominated local administration since the independance, partly because they have used their ressources to provide their children with a better education than average. Even today, they can still enjoy position of privilege and respect.

After independendance, the head (bupati) of Tana Toraja regency (kabupaten Tana Toraja) had always been hailing from the ‘princely’ districts. The split of the regency between Tana Toraja and Toraja Utara in 2008 can be partly explained by the will of the northern districts to break free from the influence of their southern neighbours.

About slavery

In the past, all the nobles had slaves, as well as some commoners and even a few slaves.

Differend kind of slaves existed : those born as slaves and usually the uncessible property of a tongkonan, the war prisoners, those who fell into slavery because of debts. Most of slaves could pay off their freedom (unless they were born as slaves), it wasn’t easy but it happened.

I found this interesting comment in Waterson : “slavery was abolished by the Dutch and reiterated in 1949 by the new government of the Republic of Indonesia. The status of kaunan has not disappeared, at least from the public memory. In some areas, the descendants of former slaves often continue in a position of marked dependence on their former masters, while in others, the relationship has genuinely been allowed to lapse, or has been eroded to the point where it is no longer significant“.

Even today, it’s difficult to talk about slavery with Toraja.

Customs

If the Toraja traditional society was very inegalitarian, on other aspects it could be described as liberal.

Divorce was easy to obtain. The responsible partner had to pay a customary fine called kapa’ which value was based on its rank.

Virginity was not required to get married. Payment of brideprice was unusual unless in the district of Bittuang.

In the days of the early Dutch administration, polygamy was still common among the nobility in the princely districts as well as Kesu’. It was common for men of the aristocracy to have affairs with women from the ranks of the commoners and slaves. Noblewomen also used to marry many times (successively).

Before the age of TV, children were the main source of amusement. It was a common practice to send a child or a younger sibling to live with an isolated grandparent.

The world according to Toraja traditions

Cosmology

Waterson reports the following version of a creation myth, told by an elder of Kesu’ district :

Out of chaos, the sky (Langi’) and Earth (Tana Padang) separated giving birth to 3 deities known as the Titanan Tallu (‘Three Hearthstones’)

- Pong Tulakpadang (‘Lord who supports the Earth’), who later went to the underworld

- Pong Banggairante (‘Lord of the broad plain’), who stayed on Earth

- Gaun Tikembong (‘Cloud that grew dense’), who went into the heavens

Together they created the sun, the moon and the stars.

Gaun Tikembong couldn’t find a wife in heaven. He made a son out of his own rib. His son Usuk Sangbamban travelled East and found his wife Simbolong Manik in a rock.

They have a child : Puang Matua (the Dutch linguist Van der Veen selected him to stand as the translation for ‘God’ in his translation of the Bible into Toraja) ‘Old Lord’ who couldn’t have child with his wife and eventually set to the West to search for gold. He found it and built a forge from which he created the female ancestor of humans Datu Laukku’, cotton, cattle, plants and trees …

Besides the human, the other creation were destined to provide for Datu Laukku’ and her descendants (she is said to have reproduced independantly), and the buffaloes and the chickens to be sacrificed as offerings. Pigs would be found later by her grandson.

The main difference between humans and animals is that humans know how to make sacrifices.

Humans continued to live in the sky for some time before the first couple Bura Langi ‘Foam of the sky’ and Kembong Bura ‘Rising Foam’ descended to Earth. The ancestors are thought to have first set foot on a place south of Duri in the South-West before crossing the mythical island of Pongko’ with eight boats.

Unfortunately “the corpus of myth in Toraja, although rich, is rapidely dwindling as its custodians (mostly aged priests of the traditional religion) die without successors interested in memorizing the heritage of oral literature which they carry” (Waterson, 2009).

Many other origin myths can be found in Nooy-Palm (vol I).

The cardinal points

Toraja gives the following meaning to the directions :

- East is associated with life

- West is associated with death and their land (the Puya)

- North is associated with the divinities of the upperworld, the most important of them being the creator god Puang Matua as well as others deities from the mythology.

- South is associated the underworld.

Cardinal points form 2 pairs that have a major importance in the cosmology and the ritual performance : upperworld/underworld and East/West

The underworld is the abode of Pong Tulakpadang who keeps the earth in balance as well as other minor gods. He does not inspire terror and is instead described as ‘full of mercy’. He is credited with the creation of the sun, the moon and the stars. “The underworld as such plays a surprisingly modest part in the religious thinking and pratice of the Toraja” (Nooy-Palm, Vol I).

People always sleep in the East-West direction. South-North is the orientation given to dead person laid to rest.

Beliefs about the afterlife

At death, the Toraja believe that a ghost of the person subsists. They call it bombo and it’s described as a kind of ethereal form that looks exactly like the person. The bombo reaches the Puya (the land of the dead) firstly through a sort of tunnel in the earth.

By performing the proper rituals, the relative of the deceased ensure that he will pass the judge and king of Puya, Pong Lalondong. If they fail to do so, the bombo is said to roam on earth and to be very dangerous for the livings. Cats are able to see the bombo.

The ideas of creamation is abhorrent. A great importance is attached to preserving the bones in the family tomb. This is believed essential to ensure ancestral blessings. The Toraja traditionaly bury their dead in stone graves, using either boulder, cavern or cliffs.

The Puya is described as a place in the South West of Tana Toraja, where life goes on very much the same as life on earth, but in the absence of fire. Sacrificed buffaloes or pigs at funerals accompany the ghost of the deceased in the Puya.

The ancestors are able to leave the Puya from time to time, to visit the house of their offspring. They can also communicate through dreams, that would later require the interpretation by a priest. Traditionaly, people would keep a small basket above the hearth of the house and place morsels of food inside at mealtimes for the ancestors.

Eventually, at the end of the mortuary rituals cycle, the bombo would be eventually purified and climb up the mount Bamba (a moutain in the Puya). From here and after the celebration of an ultimate death ritual (pembalikan), the soul can raise to the upperworld and live as a deified ancestor.

Nooy-Palm explains : “such fortune is largely confined to the rich and their relatives […]. The fate of those in whose honour only the smaller mortuary rites are celebrated, is not clear. Some may remain dangerous bombo, others stay in Puya without disquieting their relatives“. In some regions, the undertaking of the most complex level of funerals was thought to give a direct access to the upperworld to the deceased, which would not prevent the family to perform the rituals to take place after the funeral itself.

In ritual verse, the priest would sometimes chant how the ancestors eventually leave the Puya and become one with the stars, to later return on Earth as rain and thus helping the crops to flourish.

Spirits of the nature

Toraja also believe in localized spirits, who dwell in the natural world : the moutains, the rivers, stones, the wind …

Some of them live in the ground, everyone should make an offering to them before digging a hole in the ground.

Some evil spirits also exists like To Magambo’ ‘the Sower’ who is believed to be the source of smallpox. They bring calamities that are cured through feasts and purification rituals.

A short history of Toraja

The 2016 edition of the Lonely Planet states that “for centuries Torajan life and culture survived the constant threat posed by the Bugis from the southwest”, which is a slightly misleading assertion, at least if one looks at the whole history (specialists have very little clue about what happenned before the 14th century).

A more precise account can be found in Waterson :

“A number of historical incidents involving aggressive incursions of Bugis in the Toraja highlands have come enshrined in the oral memory. They have come to serve a certain purpose in defining Toraja’s identity through opposition to their neighbours.

This feeling was reactivated by the slave trade at the end of the 19th century and the Islamic guerilla in the 1950s, until it has come to obscure the long periods in which peaceful co-existence, cooperation and trade were the norm.“

The old ties with the lowland kingdoms

The older stories tended to establish positive connections between highlands and lowlands, in the form of relationships forged through mariage between noble houses in Toraja and the ruling nobility of Bugi and Makassarese kingdoms.

The Toraja language shares 45% of cognates (words with the same origin) with the Bugi language and 40% with the Makassar language.

The chronicles of Makassar (but not the Bugi epics though) mention one of the most prominent mythical ancestor of the Toraja (Laki Palaka). In some version of the Bugi myths, a Toraja man is believed to have introduced iron among the Bugis.

According to Pelras, the datu (king) of Luwu (the most sacred Bugis kindgom) must have some Toraja blood to be an acceptable candidate for office. He traditionaly wears a Toraja loincloth beneath his garments at his investiture. The puang (prince) of Sangalla is always invited to such ceremony and has to be treated with the greatest deference.

In 1983, the datu of Luwu and members of his family attended a ceremony held to celebrate the rebuilding of a famous tongkonan (Nonongan in Sanggalangi’ district). Even being a Muslim, he acknowledged himself among the descendants of Manaek (the founder of the tongkonan) and brought a large pig to show deference to Toraja customs.

The coffee war and the Dutch takeover

- In the late 17th century, the Toraja highlands suffered an invasion from a prominent king of Bone (a Bugi kingdom) sometimes identified as Arung Palakka. That led to what is maybe the first alliance between the headmen of Toraja settlements and mark the original source of a Toraja shared identity. Their alliance comprised almost all the territory that constitute today the regencies of Tana Toraja and Toraja Utara. From this period, the area of Duri and Enrekang which were still part of the Toraja world progressively converted to Islam.

A peace treaty relative to these events have been conserved by the Bugis on a lontar manuscrit. If Toraja had to send a gold tribute and raise some troops if required, the highland retained a lot of autonomy. According to the Toraja version of events, a great oath (basse kassale) was sworn between the leaders of Bone and Toraja that can be ritually awaken (ditundan basse) to bring disaster on the side who would disturb the peace.

- The end of the 19th century was another troubled period, as the lowland kingdom of Sindenreng and Luwu fought in the highlands for the control over the coffee trade, also using their presence there to raid for slaves.

Both kingdoms had closed alliance with local Big Men, most notably Pong Tiku of Pangala’ and Pong Maramba of Kalambe (near Rantepao), who collaborated in the process to gain wealth used to buy firearms and wage territorial expansion. It is estimated that 10-15% of the Toraja population was taken as slave during this period who lasted maybe 20 years.

- The highlands were eventually pacified by the Dutch takeover in 1905-1906. Contrary to the Bugis kingdoms, a majority of Toraja leaders chose not to offer resistance to them. For some of the Big Men like those quoted above, it was also a way to consolidate their recent land seizures during the coffee war.

The Dutch abolished slavery in 1909 and established a large Christian mission in the highlands who focused initially on education and medical services. They also banned headhunting but even in the litterature of the first missionaries, there are very few accounts of it. Presumably, headhunting has never claimed many victims.

There was usually 3 reasons for an headhunting expedition :

- Provide a notable dead man with a servent in the afterlife

- Avenge the death of a fellow villagers fallen in battle

- Allay an epidemic (reported once in the Mamasa region)

Until the arrival of the Dutch, the Toraja were unfamiliar with writing. Only a few Toraja had mastered Buginese, in speech and in writing.

The process of conversion to Christianity was very slow : 1% in 1930, 10% in 1950 (Nooy-Palm).

Volksman reports that “one of the great delight of Dutch colonialism was the introduction of soft, ready-made cotton cloth. Among other reasons, women liked it because they no longer had to sit for days weaving pineapple fiber at their back-strapped looms ; men liked it because it felt much nicer than coarse woven pineapple for loincloths. When cloth suddenly became scarce during the Japanese occupation, people were forced to turn again to the laborious tasks involved in processing the pineapple plant and weaving its stiff fibers“.

Post-independence events

The post-independance years were rough throughout all South Sulawesi. All over Indonesia, independance guerilla fighters were incorporated in the national army (TNI) but in South Sulawesi this process proved difficult. Some refused and instead joined forces with the Darul Islam rebellion from West Java and started to fight for the creation of an Islamic state in South Sulawesi under the leadership of Kahar Muzakkar.

The Islamic guerrilla bands roamed South Sulawesi from 1950 until 1965, including the highlands, acting like bandits. Some forced conversion to Islam cases have been reported. Many great houses have also been burned. “The aggressive behaviour of the Darul Islam bands throughout the decade played a strong part in alienating people from Islam and encouraging Christian conversion” (Waterson, 2009).

A former Muzakkar lieutenant, Andi Sose, who had chosen to join the army was positioned with a battalion in Makale but acted more like a warlord who seeked primarily money. Cases of extortion, rape and forced marriage have been reported.

On two occasions, a made-up coalition of Toraja rebels, policemen and soldiers rose against their military oppressors and defeated them in 1953 and 1958, after having awakened the ritual oath sworn in against Bone 300 years earlier.

Other articles on Tana Toraja

Toraja Culture : People and History

Toraja Culture : Aluk To Dolo

Tana Toraja Travel Guide

Sources

- R. Waterson, 2009, Paths and rivers: Sa’dan Toraja society in transformation, Leiden : KITLV Press.

- H. Nooy-Palm, 1979, The Sa’dan Toraja; A study of their social life and religion. Vol I. – Organization, symbols and beliefs, The Hague: Nijhoff.

- H. Nooy-Palm, 1986, The Sa’dan Toraja; A study of their social life and religion. Vol II. – Rituals of the East and the West, Dordrecht: Foris.

- T.A. Volksmann, 1985, Feast of Honors; Ritual and change in the Toraja highlands, Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

- C. Pelras, 1996, The Bugis, Oxford: Blackwell.

Leave a Reply