Note : I’ve prepared this article ahead of the 2019 elections. In October 2019 I added a section “The Results” at the beginning, after the official results were published.

The results

I retrieved the official results from Electoral Commision (KPU) on October 13th (based on 99,5% of the ballots cast).

Here is how the big pictures evolved between 2014 and 2019 :

A good campaign from Prabowo

At first glance, Prabowo seems to have done better virtually everywhere compared to 2014 :

- He shifted Jambi, Bengkulu, South Sulawesi and Southeast Sulawesi.

- He reinforced his lead in Riau, South Sumatra, West Sumatra, Aceh, Banten and South Kalimantan

- He reduced the gap in virtually all others parts of Sumatra and Kalimantan, as well as DKI Jakarta.

Many have speculated that Jokowi lost votes in Sumatra and Kalimantan because of the low prices of agricultural commodities on global markets.

In Aceh, it is possible that the absence of Jusuf Kalla (the 2014 vice president) had an effect on the voters (Kalla was involved in the peace process in 2000s).

In South Sulawesi, as expected, the replacement of Kalla (a native of South Sulawesi) turned the usually conservatives voters away from Jokowi

The only thing is that an Indonesian election is won in Java. And Jokowi smashed Prabowo there.

Reasons behind Jokowi’s success in Java

In 2014, Jokowi had secured a 8Mio votes lead in the ethnic Javanese provinces of Central Java, East Java and DI Yogyakarta while he was lagging 5,4Mio votes behind Prabowo in more conservatives Banten and West Java.

In 2019, Jokowi scored 20,5Mio votes more than Prabowo in Central Java, East Java and DI Yogyakarta while trailing Prabowo by only 6,8Mio votes in Banten and West Java.

Jokowi was already highly popular in Central Java in 2014, as he is the former mayor of Solo. He further increased his lead in 2019, indicating that the Javanese are satisfied by his terms, but it is in East Java that his progress were the more dramatic.

The most direct explanation is probably his pick of Ma’ruf Amin as vice-president. Ma’ruf Amin is the chairman of Nahdlatul Utama (NU), the largest Muslim public group of Indonesia.

Everyone focused on the fact that he picked an Islamic scholar during the campaign, but retrospectively it is maybe the NU factor that was the most important.

NU is closely associated to East Java, while Muhamadiyah are stronger elsewhere. By picking a NU vice-president, Jokowi sent a strong message to East Java, and based on the results he got an answer.

How to elect an Indonesian president ?

On the 17th April 2019, 193 millions of voter (out of a population of 262 millions in 2017) were called to the booth for 5 simultaneous elections. Indonesian voters have had to pick their new president, renew the upper and lower legistlative assembly (DPR and DPD) and in relevant areas renew provincial legislatures as well as municipal or district legislatures.

Logically, most eyes were set on the presidential election which has decided who was to lead the country from 2020 to 2025.

Since the fall of Suharto in 1998, Indonesia has become one of the largest democracy in the world, electing every single representatives from local to national level through direct elections.

To become an official candidate, one must first demonstrate the support of one or several political parties that can claim either :

- 20% of the seats at the DPR (Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat or People’s Representative Council ie the national legislative assembly)

- 25% of the votes at the last elections

This first condition is usually not an issue given that there have always been only 2 candidates facing each other with the support of large coalitions behind them. However it introduces us to the importance of political alliance behind each candidate.

When it comes to the actual election, the system is a first past the post with a regional condition :

- The winner must get more than 50% of the overall votes

- The winner must also win half of the provinces and get at least 20% of the votes in the remaining provinces. This is not that hard to achieve given that there is usually only 2 candidates. It’s a safeguard included in the 1945 Constitution to maintain the unity of the country.

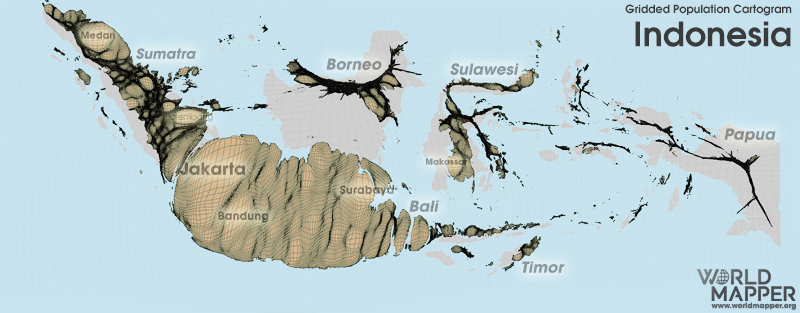

That’s it for the official rules. Now let’s introduce one very important factor : Indonesia population repartition.

Given that inhabitants of Java island account for 57% of the population, it is obviously in Java that an election is won or not (see my introduction to Indonesian demography for more details). Nevertheless, results are not uniform between each of Java’s provinces.

2014 election repeated ?

At first glance, the 2019 presidential election looks like the rematch of 2014 given that it opposes the same 2 candidates : Joko Widodo (universally called Jokowi) versus Prabowo Subianto (usually refered to as Prabowo).

But let’s not overlook the following factors :

- Both vice-president candidates have changed.

- In 2014 both candidates were running for a first term. This time, Jokowi is the incumbent president, with a proven track record behind him.

Now I will try to analyse Jokowi’s 2014 victory and identify the reasons behind it.

The 2014 campaign

The 2014 elections appeared to many as the opportunity to usher a new era in Indonesian politics.

The first candidate was Prabowo Subianto, former General of the army’s special forces (Kopassus) and former son-in-law of Suharto (he divorced his daughter in 1998). Besides that, Prabowo is the son of Sumitro Djojohadikusomo, one of the richest indigenous businessman of the Suharto era (along the families of Edi Adiwinata and of course Suharto), who assumed multiple Ministry positions during the New Order.

Prabowo campaigned about the nostalgia of Suharto’s regime (the New Order) which brought undeniable political stability and strong economic growth. He pictured himself as the strong man Indonesia needed to rule its corrupted elite.

Prabowo faced Jokowi, a young politican from the new generation, not very charismatic but with a reputation of getting things done. His good track record as mayor of Solo (Central Java) and Governor of Jakarta made him nationally popular. He originally made his career in the furniture business and didn’t have any tie to the old regime of Suharto.

When Suharto fell in 1998, Indonesia leaders engaged their country into a smooth and relatively peaceful transition to democracy, a reform movement known as the reformasi. This choice implied that Suharto-era figures have mostly been left in place and asked to take part in democratic elections and institutions. Freedom of speech and association has returned in Indonesia, but most of the New Order’s old figures are still there. Through his background, Prabowo embodied this old elite who had successfully adapted to the new democratic rules.

So in one sense, the 2014 elections raised the issue of continuing or not on the path of reformasi. Jokowi was the potential first elected president absolutely foreign to the New Order. High hopes were vested in him to reform the inheritage of Suharto’s era : inefficient and corrupted states institutions (bureaucracy, justice, police, army).

With the return of democracy, hard-line Islamists, who were suppressed under both Sukarno and Suharto, have been allowed as other civil groups to voice their concerns. As a consequence, debates going back to the Indonesian independence about the role of Islam in the state and society have been reignited. Prabowo tended to court this voting group, while Jokowi’s moderate Muslim credentials helped him to secure the support of the minorities.

Jokowi’s pledge to improve fiscal performance and to suppress subsidies on gas in order to finance infrastructure building were also quite popular in the Outer Islands.

Jokowi’s 2014 victory

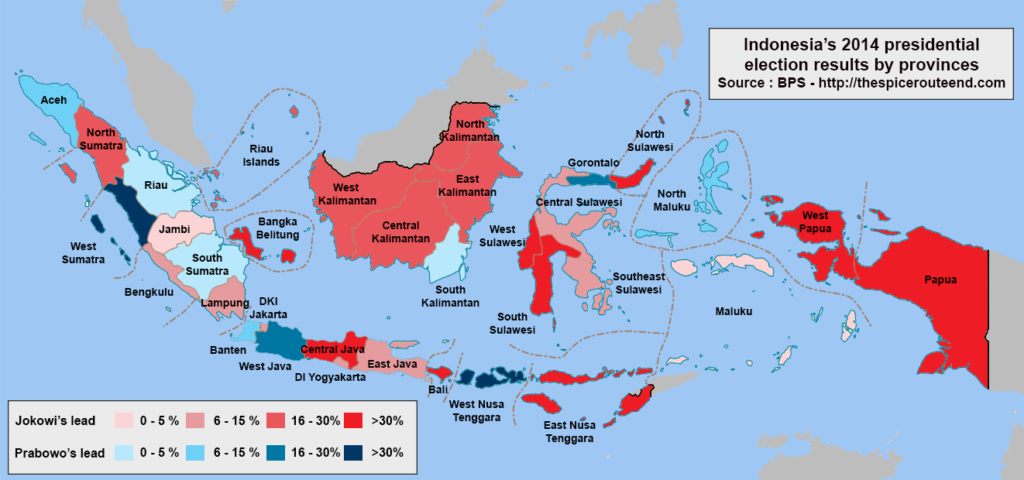

In 2014, Jokowi won about 53% of the votess cast. His lead was above 8 millions votes.

The basis of his victory was his very high popularity in his home region of Central Java where he obtained a 33% lead over Prabowo.

His “home advantage” added to good performances in East Java (6% lead), DI Yogyakarta (12% lead, similar sociology to Central Java) and DKI Jakarta (6% lead) allowed him to fully offset Prabowo’s good performances in West Java (20% lead), Banten (14% lead), West Sumatra (54% lead) and NTB (32% lead).

At this point of the counting, Jokowi and Prabowo scores are rather balanced. But Jokowi also scored big in South Sulawesi (43% lead or 1,8Mio votes), West Papua (43% lead or 1,3Mio votes), all provinces of Kalimantan but the South (another 1,3Mio additional votes versus Prabowo), Bali (43% lead or 0,9Mio votes), NTT (32% lead of 0,7Mio of votes) and North Sumatra (10% lead or 0,7Mio of votes).

How to explain 2014 votes by province ?

We may consider the economy of each province through the proxy of their Gross Regional Products but I don’t find this filter very convincing :

- The poorer provinces of East Indonesia have voted massively for Jokowi but the poorest of all (North Maluku) went to Prabowo.

- In Sulawesi Prabowo won only the poorest province : Gorontalo.

- In Java, Jokowi won both the poorest regions (Central Java and DI Yogyakarta) as well as the richest (DKI Jakarta).

A more powerful factor seems to be the religious sociology of each province :

- Jokowi won all the provinces with a non Muslim majority as well as almost all those with a non Muslim minority representing over 10% of the population but Gorontalo (where he lost by 26%) and Riau and Maluku (where he lost by less than 1%).

- Prabowo got his best scores in Muslim conservative provinces : Aceh, West Java, NTB and West Sumatra.

Yet Jokowi smashed Prabowo in South Sulawesi, which is also quite conservative. Here, we can introduce another important factor : the candidates’ ethnicity. Without a doubt, Jokowi’s win in South Sulawesi owes much to his vice-president : veteran politicians hailing from South Sulawesi Jusuf Kalla. And the large population of Central Java voted massively for Jokowi because he is an ethnic Javanese.

From the campaign to power

Yet it would be naive to only consider Jokowi as the candidate of the people and Prabowo as the candidate of the elite. Indonesian politics is very complicated and based on coalition and consensus

Prabowo was Megawati’s running mate in her unsucessful bid to presidency in 2014. Megawati is the chairman of PDI-P, the same party that nominated Jokowi to face Prabowo in 2014.

Jokowi picked Jusuf Kalla as a running mate in the campaign, who notably served as elected vice-president under SBY’s first term. Prabowo’s own running mate Hatta (SBY’s in law) initially hopped to be picked by Jokowi !

Jokowi’s term

Strong but non inclusive economic growth

Jokowi has repeatedly promised to achieve 7% of economic growth throughout his term. He actually managed to achieved a steady 5%.

Inflation was kept under control and despite a clear decreasing trend, the value of the Indonesian Rupiah on exchange markets remained acceptable.

So by looking at the macro numbers, his term looks rather sucessful when it comes to the economy. Yet, have those statistics translated into tangible benefits for the population ?

From the 1990s and the end of Suharto’s regime, revenue inequalities have increased in Indonesia. The Gini ratio reached 0,4 in the 2000s (versus an average of 0,35 before the Asian Financial Crisis). Under Jokowi’s term, inequality have been slightly reduced but not enough to have tangible effects on the entire population (Indonesia at Melbourne).

Despite various social assistance programs, the consumption of the poorest 20% of the population has grown slower than the economy (East Asia Forum). This suggests that the poorest portion of the Indonesian society had not benefited much from the economic growth under Jokowi’s term.

Jokowi also failed to reduce the share of informal jobs in the labour market, quite stable around 58% in 2017 (Ministry of Labour). The active population was about 117Mio people in 2017.

This doesn’t mean that the Indonesian economy doesn’t create any jobs. In facts, nearly 10Mio new jobs have been created during the past 10 years, but in the meantimes a huge number of young Indonesian have been added to the labour force

It is then not very surprising that many people feel disappointed by Jokowi’s term, lamenting their exclusion from the country’s undeniable growth.

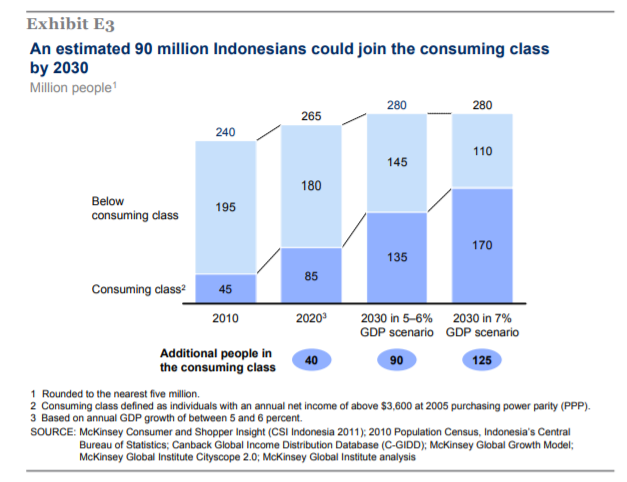

I like the following chart from consulting firm McKinsey published in 2012, figures are probably not up to date but it’s still pretty telling about the reality of the Indonesian society. The consumming class refers to the households that are able to spend on other things than their basic needs. The interesting part here is the portion of the population “below consuming class”.

The push on infrastructure

Jokowi’s key policy has always been infrastructures development. Among his most striking promises, he pledged to build 35,000MW of electrical production capacity and 1000km of new toll roads.

As of December 18, only 2,899MW capacity was operational. Yet another 18,207MW were already under construction (CNBC Indonesia). The original target will be missed but it’s not a big deal given that it was likely an overshoot (national electricity company PLN slashed his new production development target by 22,000MW in 2018 due to lower demand, Jakarta Post).

Besides production capacity, the government has also heavily invested in the distribution network. The electrification rate of the country has progressed from 84,35% in 2014 to 97,5% in 2018 (CNBC Indonesia). This may sound modest but those % are to hardest to achieve, because it means bringing infrastructure to remote and sparsely populated areas. Only 60% of the population of the poor provinces of Nusa Tenggara Timur or Papua have currently an access to electricity (PwC Indonesia)

Over 600km of toll roads had been inaugurated already by 2018, a notable performance compared to the previous tenure of president SBY who had built only 250km during this 10 years leading Indonesia (BPJT).

I believe that Jokowi scored precious points during the 2018 Ramadhan exodus known as Idul Fitri. Transports time from Jakarta to other parts of Java have been way below standards thanks to newly opened toll roads (BBC Indonesia).

Besides that, the government has renovated or built many airports, frontier posts and harbors (Detik Finance). Jakarta has just inaugurated Indonesia’s first ever city underground public transport, a project that Jokowi had personnaly initiated while he was still the capital’s governor.

Those infrastructures have been mostly financed by debt isolated out of the state budget in the books of state-owned companies (like PLN or civil contractors such as Wika).

Jokowi pledged during the 2014 to re-allocate the public subsidies for gas to infrastructure development. Yet subsidies have been suspended only for a couple a month.

Despite notable progress, the tax-collection performance of the Indonesian state is still very low. There are only 18,3Mio of taxpayers number issued for a country of more than 250Mio inhabitants

Other important topics

The agrarian reform

The government estimates that 126Mio plots of land has long been lacking legal certification. Only 46Mio of them were certified when Jokowi took office. According to the current government, the standard performance was 0,5Mio certificates issued each year prior to them.

From 2017 to 2018, the government issued about 15Mio certificates and aim at finishing the job around 2023 (CNN Indonesia).

Economic nationalism

Jokowi spared no efforts to nationalize some major economical assets : the Indonesian state forced US mining giant Freeport McMoran to sell 50% of their stake in the mine of Grasberg in Papua (one of the world’s 5 largest mine for both gold and copper), it didn’t renew the exploitation licence of French Total and US Chevron in the blocks of Mahakam and Rokan allowing national oil & gas company Pertamina to take over. The Indonesian subsidiary of cement giant Holcim was also sold to a state-owned company

The deforestation issue

In the wake of the severe forest fire episode of 2015, Jokowi’s government issued a moratorium on the draining and the clearing of peatland, which had a positive effect on the severity of forest fires in the following year. Yet the main explanation is probably that 2016, 2017 and 2018 were simply not an El Nino year (which induced a more severe drought dury the dry season).

Deforestation is slowing but still ongoing. Yet some encouraging steps have been taken : the merging of the Ministry of Environment and the Ministry of Forestry, the first-ever unified land-use map of the country or the ever increasing prosecutions of environmental crimes (I have adressed this topic in much more details in the last sections of this article).

The National Health Insurance program

The Jaminan Kesehatan Nasional or JKN (usually referred to as BPJS from the name of the public agency administrating it) is now one of the largest healthcare program in the world, with 195,2Mio members.

While employees and independent workers pay premium by contributing a share of their wage, the government pays what is due by low-income members. About 60% of BPJS members received a subsidy from the government.

BPJS has been in heavy deficit since its inception in 2014, due to difficulties to collect the premium due. In 2017 it posted a deficit of $1,2bn that is funded by the state budget. Many hospitals are reluctant to collaborate with BPJS and several Indonesian are also wary to contribute to BPJS ; they often deem it unreliable to provide them with reimbursments in time needed.

Despite serious shortcoming, BPJS has provided free healthcare to many poor families for the first time. Resolving its funding issue is essential to make it sustainable.

The BPJS is not a creation of Jokowi, actually it was set up by the end of its predecessor term. Yet it’s Jokowi who had to deal with the deficit issue. So far he mostly delegated this topic to the BPJS agency and the Ministry of Health, refusing to make the scheme compulsory or to raise the premium.

Jokowi’s normalization

In 2014, Jokowi was clearly the darlings of foreign journalists who built up a hype around him similar to the one Obama had during his first campaign. He was supposed to bring justice, democracy and equality to the Indonesian society. Of course he couldn’t live up to such expectations.

I think that most of this issue comes from an original misunderstanding of the Indonesian political game. It doesn’t take one man to change a system

It is nonetheless important to stress that Jokowi was never at any point embroiled in any kind of scandal or corruption case. The fact that neither his wife or his children seems to be interested either in politics or serious business is also quite refreshing in a country as clanic as Indonesia.

Yet, Indonesia can only be ruled through alliance and compromises. Like his predecessor Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (another former Suharto’s general), Jokowi formed a large coalition to rule the country and pass bills at the parliament. By doing so he traded some independence for stability.

Jokowi has also his own supports within the army. Prabowo is often critized for his implication in the shootings of student in 1998 but Jokowi welcomed in his government former General Wiranto and Luhut Pandjaitan who were accused of implication in the war crimes committed during the invasion of Timor Leste.

He didn’t hesitate either to foster the sympathy of the voters by capping electricity or gas prices or by increasing the duration of the holidays for civil servants.

Jokowi’s image after 5 years as a president is now more or less similar to other Indonesian politicians.

Jokowi’s failures

Jokowi has rather failed to adress the rising intolerance between various religious communities. His personnality which incites him to avoid open confrontation has proven a weakness on this issue. Sectarian and identity politics are stronger than ever in 2019

Persecution of minorities is still a reality in today’s Indonesia, whenever they were Ahmadiyas in Lombok or Christian churchgoers in Jambi. Jokowi never step up in such cases

Many initial supporters have also lamented the drifting away of Indonesia from the rule of law. Jokowi’s government has repeatedly cracked down on opponents using some of Indonesia most vagues laws such as the 2008 law on cybercrime.

Despite prosecuting more cases than ever, the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) has not received the expected support from the executive power.

The bureaucracy has been only slightly reformed, despite efforts to improve the governance of state-owned enterprise or to cut down the processing time for business licences

The Papuan question was only adressed through the issue of infrastructure development. Military operations are still ongoing in this part of the country.

Eventually, the education sector has made very few progress. Indonesian students are still well behind their counterparts in neighbouring countries in international benchmarking. Teachers are underpaid and ill-trained, the administration is corrupt and the volume of class given still quite low.

2019 campaign

Jakarta’s governor election sequel

2017 Jakarta’s election were by far the most significant political event of Jokowi’s term.

Jokowi had left the position to his deputy governor Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (known as Ahok) in 2014 when he was elected president. Ahok campaigned to get elected on his own name in 2017, facing former Jokowi’s Ministry of Education Anies Baswedan and previous president SBY’s son Agus Yudhoyono.

Ahok was eventually swept away by a terrible campaign spearheaded by radical islamic groups who constantly attacked his double minority status (ethnic Chinese and Catholic). Banners flourished in Jakarta exhorting Muslims voters not to pick an infidel (kafir) as a leader.

Ahok eventually paid a much higher price than the simple political defeat because he got convicted to 2 years in jail for a blasphemy. He was released only in early 2019 and has adopted a low profile since then.

It was very clear that the battle for Jakarta was only the warm-up for the upcoming battle for the presidency two years latter. Yet Jokowi managed to limit personnal damages by not implicating himself in the Jakarta’s elections.

Behind the scene, the spiritual leader of the Islam Defenders Front (Front Pembela Islam or FPI) was somehow forced to seek something close to exile in Saudi Arabia so as to escape various trials he was suddenly facing in Indonesia. The government also disbanded the Indonesian chapter of Hizbut Tahir, an organization advocating the transformation of the Republic of Indonesia into a caliphate.

The choice of Ma’ruf Amin as running mate

A popular analysis is to explain the rather suprising pick of Ma’ruf Amin as Jokowi’s new running mate by a tactic to prevent any attack on religious grounds during the election.

Amin is one of the most prominent Muslim figures of Indonesia. He is the chairman of both Nahdlatul Utama (NU), the largest Islamic civil group of Indonesia with close to 40Mio members, and the Indonesia Ulama (Muslim scholar) Council.

Yet I not fully convinced by this view.

Opinion polls show quite clearly that Jokowi is viewed as a more pious Muslim than Prabowo (Jakarta Post). The former general’s mother is not even Muslim but Protestant. When it comes to Sandiago Uno (Prabowo’s running mate), it’s is amusing to note that he attended Catholic schools since childhood (something not unusual among kids from a rich background, including Muslim).

Just to give another example : Prabowo never married again after his divorce in 1998 which is a clear disadvantage in such a family-oriented society as Indonesia.

What I’m trying to point out is that there were plenty of potential vicious answers to a smear campaign like the one Jakarta had known in 2016.

Jokowi has faced attacks on religious grounds since at least his election in Jakarta in 2012. I guess that he had learnt how to manage them a while ago already.

During the past 2 years, Jokowi developped his relationships with various Muslim communities : he visited many coranic schools (pesantren), invited and met muslims scholars (ulema) and elders (kyai). He was also able to get the support from 2 very popular Muslim personnalities : the most popular preacher of the young generation Abdul Somad and the governor of NTB province which is also a muslim scholar Muhammad Zainual Majdi (known as TGB).

My personnal theory is that Jokowi didn’t need Amin as a Muslim figure to win. Virtually no one had foreseen the pick of Amin as VP, everyone (including Jokowi) was going for Mahfud MD (an Islamic party politician and former head of the Constitutional Court). But other parties from his coalition feared that Mahfud would use his term as a platform to run for president in 2024. Hence already old Amin was picked to please everyone.

Prabowo has publicly courted the most radical Muslim groups since 2016, which has in return alienated him even more from the minorities. I believe that all the minority-strong provinces will keep voting for Jokowi because he is seen at least as the lesser evil.

I also feel that the religion is much less a topic in this campaign than it was in 2016 or 2018. Prabowo is attacking Jokowi on commodity price, public debt or the governance of state agencies.

I’m wondering if it wasn’t exactly what Jokowi has wanted. Jokowi is a PDI-P politician, his DNA is nationalism. In Indonesia this translates also into preserving the fragile unity of the archipelago as the Republic of Indonesia.

With Amin on his side, Jokowi ensures that all the polarizing issues are put under the rug for the moment. He buys some time until his reforms gain enough tractions during his second term to generate income growth for the whole population. Five years latter, with everyone better off economically, tolerance rise again in the Indonesia society. I’m probably daydreaming but that would be a very Javanese way to deal with the current state of the Indonesian society.

The campaign

Jokowi’s main message during 2019 was that he had a proven track record behind him (kerja nyata), that he had demonstrated his capacity to get things done and to push Indonesia forward (Indonesia maju).

Prabowo has repeatedly lambasted an alleged inflation in commodities price while pledging to get prices of various goods such as eggs, rice, peppers down (without clearly explaining how he intended to do it).

He also denounced the foreign interests in Indonesia, whatever they were foreign investments buying up Indonesia’s infrastructure, imports jeopardizing Indonesia’s production or foreign workers stealing jobs from Indonesian.

My personal expectations

Every single poll issued since the beginning of the campaign has given Jokowi as a large winner.

Jokowi will definetly secure a very large lead in Central Java again. DI Yogyakarta will most likely follows.

Given the results of the 2018 governor elections in East Java, it is also reasonnable to assume that he will win again this highly populated province.

DKI Jakarta’s results will be interesting, Jokowi won in 2014 but it’s the candidate supported by Gerindra (Prabowo’s party) who won in 2016’s governor election. In North Sumatra, the candidate of the PDI-P was also defeated during the 2018 governor election.

On the other hand, it is not certain that Prabowo will be able to maintain his 2014 lead in Banten and West Java too.

In 2018, it’s the former mayor of Bandung Ridwan Kamil who got elected governor of West Java. He is an architect, usually considered as a moderate Muslim and he also picked a rather conservative as a running mate. Jokowi’s team has also campaigned a lot in the province during the previous months. Recent polls suggest much closer results this time.

Jokowi won by a landslide the highly-populated province of South Sulawesi in 2014, but he had a Bugi as a running mate which definetly helped a lot. He’s running without him this time so it’s going to be interesting.

Thank for your articles

Thank you. Very interesting