Sumatran tigers are the last non-continental subspecies of tiger (meaning that they are not found on the Eurasian mainland) but also the smallest and the rarest of all tiger subspecies.

Species factsheet

Characteristics

Adult males can reach 2,5m and 140kg and females 2m and 90kg.

The Sumatran tiger is the apex predator of Sumatra, feeding mostly on wild pigs, muntjac and sambar deers as well as pig-tailed macaque. It is also a cryptic and solitary animal that is known for its very large home range.

Its life expectancy is about 15 years in the wild. Tigress gives birth in about 103 days to usually 2 or 3 cubs but sometimes up to six.

Habitat

The Sumatran tiger is endemic to the island of Sumatra in Indonesia.

In the past, other subspecies of tigers roamed Indonesian forests, but both the Bali and the Javan tiger have been brought to extinction in 1940s and 1980s respectively.

It is capable to adapt to a wide range of environments provided that prey and water are available. Yet if Sumatran tigers pugmarks have been found above 3’000m in the moutains of the Gunung Leuser National Park (Wibisono 2010), its prime habitat is lowland and hill forests that can host population density 10 times higher.

The Sumatran tiger is listed as critically endangered by the IUCN since 1994 and is a protected animal by Indonesian law since 1990.

Current threats to Sumatran tigers

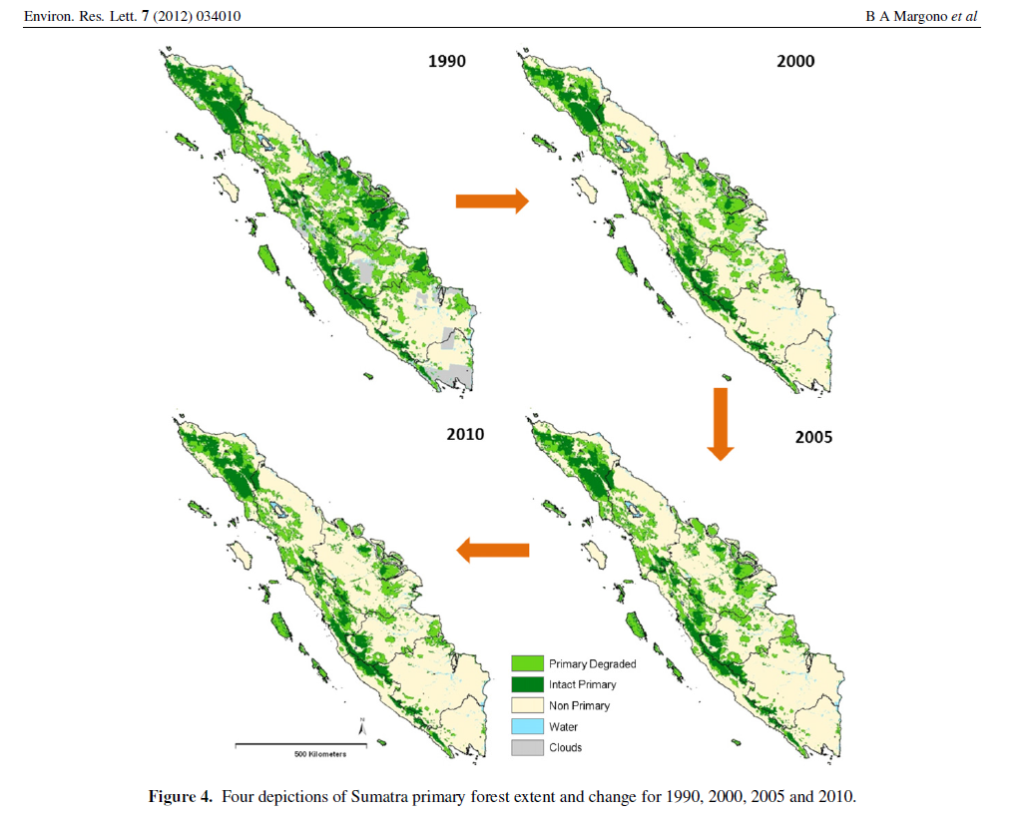

Deforestation in Sumatra

The main cause behind the decline of the Sumatran tiger is primarily habitat loss and fragmentation. I have already written an extensive article about deforestation in Indonesia and its causes, so I won’t dwell upon this issue here.

The impact of forest clearing is reinforced because it focuses mostly on lowland forests, the land which is the most suitable for conversion to agriculture. Yet this kind of forest also hosts the highest density of Sumatran tigers.

Increasing human-tigers conflicts

As agriculture (by smallholders or larger plantation operators) encroaches on natural forest, more human settlements are built on forest edges while tigers are left to live on shrunken plot of forest.

The logical result is increased conflicts between humans and wild tigers that attack villagers (regularly injuring and killing them) and prey on their livestocks.

Nyhus and Tilson have reported 146 cases of people killed by tigers between 1978 and 1997.

Recently the Indragiri Hilir regency in Riau provided a vivid example of the conflicts arising from large-scale forest conversion in an existing tiger habitats :

- Between January and March 2018, a tiger repeatedly attacked workers of an oil palm plantation, two of them died from their injuries. After a 107 days hunt, the BKSDA Riau finally managed to capture the female, named Bonita, and to transfer her to Dharmasraya rehabilitation center in West Sumatra (Mongabay).

- In November 2018, a 3 years-old male tiger with snare injuries was seen eating villagers’ chicken and goats and was later found hiding under a shop on Burung Island. The animal, named Atan Bintang, was also captured by the BKSDA and sent to Dharmasraya.

- In March 2019, villagers from Kecematan Gaung were attacked by a tiger while transporting timber. Later captured and send to Dharmasraya (Jakarta Post).

- In August 2019, a 36-years old man was mauled to death by a Sumatran tiger in a concession area in Kecamatan Gaung (Jakarta Post).

Similar headlines can be found concerning Jambi or North Sumatra.

Illegal hunting

Despite being a protected species, Sumatran tigers suffer heavily from killing, whether from professional poachers, by getting caught in snares laid out for bush meat or by villagers seeking revenge.

A 2004 report published by TRAFFIC concluded that :

- Sumatra remained a “substantial market” for tiger parts.

- Most tigers were killed by professional or semi-professional hunters using wire cable leg-hold snares. They did not hesitate to hunt deep inside national parks.

- The authors identified poaching as the main source of decline of the Sumatran tiger (more recent studies quoted below claim that this is not the case anymore).

The report also estimated that in the late 90s, early 2000s, about 45 tigers were killed each year.

The 1990 conservation law allows a maximum sentence of 5 years in jail and 100 millions IDR fine for wildlife traffickers, but courts often pronounce lighter sentences, even though the trend is towards harscher punishment nowadays :

- Several men got sentenced bewteen 6 month and 3 years of jail in 2016, plus additional fines between 10 and 50 million IDR (Mongabay).

- In April 2017, two wildlife traffickers caught with tiger skins were sentenced to 8 months of prison in Aceh (Mongabay).

- In October 2018, the most severe sentence to date for a similar case was given : 4 years of jail and 50 millions IDR fine. Earlier in 2018, 5 men were convicted to 3 years in jail and 50 millions IDR fine in a similar case (Mongabay).

It is hard to tell if those cases are the sign of increasing poaching or better results obtained from anti-poaching teams. Anyway, NGOs are campaigning for revising the 1990 law in order to increase sanctions against offenders.

Despite being still a reality, Luskin concluded in 2017 that poaching was not anymore the dominant threat to tigers but loss and fragmentation of habitat. His main argument was that tiger density was actually increasing within protected areas.

How many Sumatran tigers are left in the wild ?

The complex task of estimating

Due to its secretive nature, low density and very large home-range population survey of Sumatran tigers are notoriously difficult if not impossible. The first area-specific population assessments actually go back only to the the late 90s.

Nowadays, camera trap surveys are the main tool used for population studies.

The paper from Wibisono & Pusparini provides an interesting overview of the research on Sumatran tigers, starting from the 70s. Besides the difficulty of actually measuring one single tiger population, the second issue to come up with a global population estimation for the entire Sumatra islands.

Researchers can usually only survey a few areas, so it is necessary to consolidate several surveys to get the big picture. This process is unfortunately very error prone (because only a few limited surveys are available, with different methodologies).

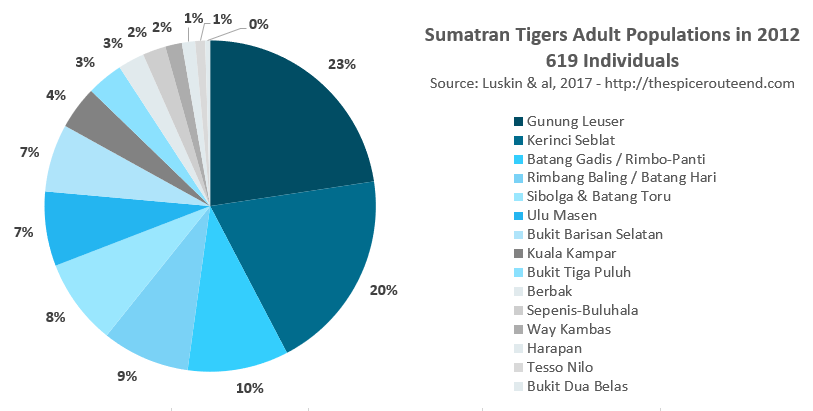

The situation as of 2012

The most recent detailed population assessment I found was led by Luskin and published in 2017. Their research was based on camera trap surveys carried out in Kerinci Seblat, Gunung Leuser and Bukit Barisan Selatan as well a statistical model they developped.

Their conclusions are :

- A population of 742 adult tigers in 2000

- A population of 618 adult tigers in 2012 (between 328 and 908).

If we try to cross check data :

- The 2008 population assessment of the IUCN estimates the Sumatran tiger population between 441 and 679 mature tigers.

- The 2016 population assessment carried out by the Indonesian government estimates the population of wild tigers to 604 indivuals spread over 23 locations (Mongabay).

Tigers populations in Sumatra

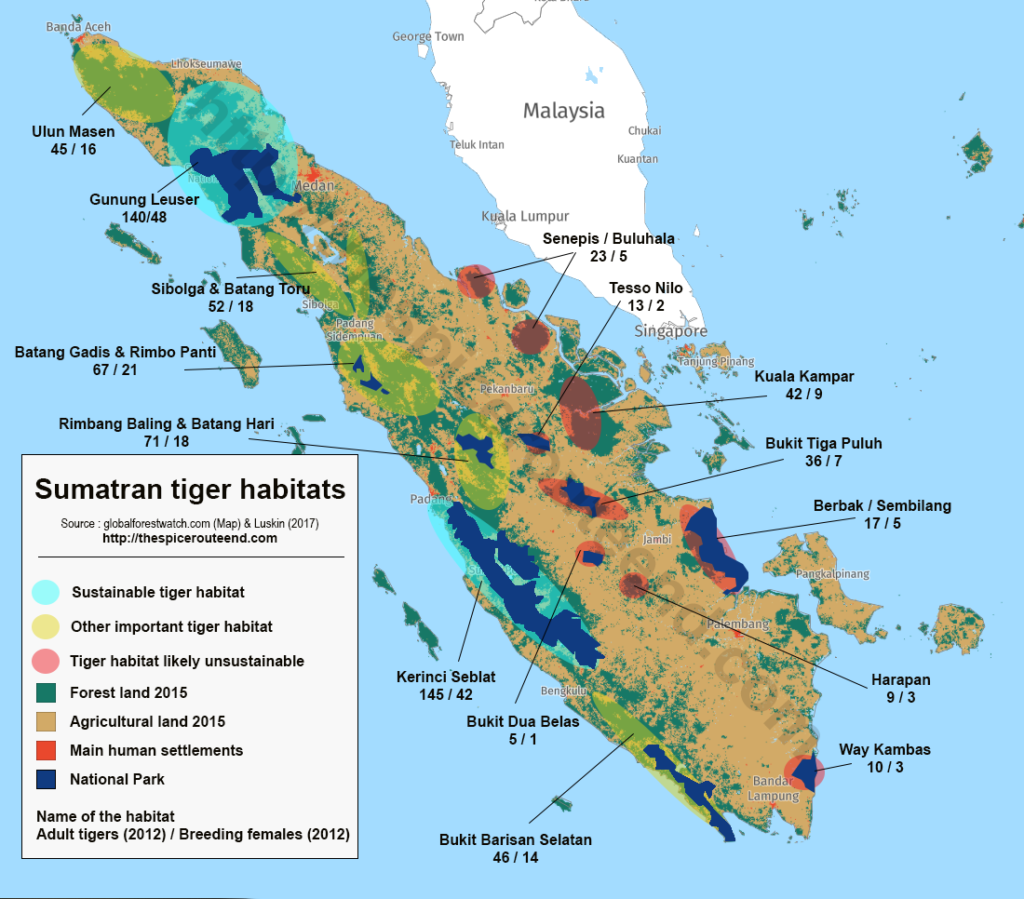

The issue is that those tigers are scattered in various habitats or various size and level of encroachment.

The global tiger conservation strategy is to preserve “Secure Source Populations” (SSP) with more than 25 females. In 2012, Luskin concluded that the only existing SSP were Gunung Leuser and Kerinci Seblat. All other known habitats didn’t have enough female to be sustainable on the long run.

Three other habitats were nonetheless close to qualify (with a mean estimate of 18 to 21 females) : Sibolga and Batang Toru landscape, Batang Gadis and Rimbo-Panti landscape, and the Rimbang Baling and Batang Hari landscape.

In the mid-20th century, 12 SSP potentially existed. Luskin’s statistical model shows that mean tiger density increased from 1996 to 2014. This suggests that the main driver of tiger’s population decline is now the disappearance of its habitat, mainly in Jambi, Riau, South Sumatra and Bengkulu.

Do we have a plan ?

The scientist recommendation (Luskin)

According to Luskin, the most crucial habitats of the Sumatran tigers are Gunung Leuser and Kerinci Seblat, where the two last remaining sustainable populations of Sumatran tigers are found. “Provided future deforestation and poaching is controlled, each of these parks could maintain >40 breeding females and likely persist without supplemental breeding programs for >200 years“.

Luskin suggests to focus other conservation efforts on four other potential SSPs that probably shelters around 20 females at the moment :

- Sibolga & Batang Toru (North Sumatra)

- Rimbang Baling & Batang Hari (Riau) : could potentially be connected to Kerinci Seblat NP by natural wildlife corridors.

- Bukit Barisan Selatan lanscape (the National Park plus Tambling Wildlife Nature Conservation and Bukit Bulai) in Lampung because of the high tiger density found there as well as strong anti-poaching policy enforced.

- The Ulun Masen landscape (Aceh) is also interesting because of its existing natural connection to the Gunung Leuser ecosystem.

If I read between the lines, it means building a tiger’s lifeline along the Bukit Barisan mountain range. This is where most of the primary forest of Sumatra remains, the issue is that most of it is montane forest, hence having a low tiger density. Preserving the lowland forests of these regions is definetly the hardest challenge.

In the province of Riau, habitats outside the Rimbang Baling / Batang Hari landscape (on the west side of the province) would probably disappear. Given the current level of encroachment of pulp & paper and oil palm estates in this region, this seems rather likely anyway (the regency of Indragiri Hilir we have talked about earlier is in Riau).

What the government says

The government’s strategy, as presented in this article, is to :

- Develop pockets of habitat suited for tigers

- Increased sanctions on wildlife regulation offenders

- Expand rehabilitation centers’ operations for tigers captured following a human-conflict. Tiger are then to be reintroduced in wildlife reserves.

Based on the 2016 population viability assessments conclusions of 604 Sumatran tigers in the wild, the government has set a 10% increase in population as target for 2019. I haven’t found officials figures about whether or not the target is going to be achieved.

Sumatran tigers in captivity

The Indonesian government has developped a policy to deal with human-tigers conflicts. If possible tigers are lured back to the forest (most of the times with firecrackers). In case of attacks, tigers are captured and then brought to one of the 3 rehabilitation centers in Sumatra :

- Barumun Nagari Wildlife Sanctuary, North Sumatra, Kab. Padang Lawas Utara (near Barumun Wildlife Reserve).

- Tambling Wildlife Nature Conservation Center, Lampung (near Bukit Barisan National Park).

- Pusat Rehabilitasi Harimau Sumatera Dharmasraya, West Sumatra (between Kerinci Seblat and Rimbang Baling). Managed by the Asrari Djojohadikusumo foundation.

Tigers rescued from traps are also brought to those conservation centers. The idea is to rehabilitate captured tiger and then re-introduce them in the wild after they are equiped with GPS collar in order to be able to recapture them for inbreeding if necessary.

It is possible to breed Sumatran tigers in captivity :

- 2 cubs were born in Barumun Sanctuary (North Sumatra) in 2018 from 2 tigers rescued after getting caught by snares.

- In early 2019, 3 cubs were born in Sidney’s zoo (source).

Short review of major tiger habitats in Sumatra

Gunung Leuser National Park & Ulu Macen Ecosystem

Nowadays the Leuser Ecosystem is the largest remaining patch of forest on Sumatra. Most of it falls within the province of Aceh, but a smaller part belongs to North Sumatra.

The reason behind the relative preservation is the rugged topography of the province, which makes it less suitable for agriculture but also the separatist movement that opposed independance militants and the Indonesian army until 2004.

On top of that, an existing natural connections still exists with the Ulu Macen landscape found further up north in Aceh

Provincial government of Aceh has vowed to safeguard the Leuser Ecosystem and has declared that there will be no infrastructure projects developped inside the National Park.

But the pledges apply only to the park, which is only ⅓ of the Leuser Ecosystem. Environmental NGOs (like Walhi or Haka) constantly opposes development plans for infrastructure projects :

- Many geothermal plants are in discussion for instance in Jaboy, Seulawah and Bumi Telong. The plan in Hitay has been revoked by the governor.

- 2 other large hydroelectric plants are being developped : a 428MW one in Gayo Lues district (requiring 40,9 km2 of land, 30% falling within protected forests, ) and a 180MW in the Kulet peatland of South Aceh (requires 4,4km2 of land, most of it belonging to the Leuser Ecosystem). The licence of the Gayo Lues project was revoked in August 2019 (Mongabay).

Encroachments from oil palm developpers as well as smallholders is still happening in the region, but not on a very large scale.

According to the BKSDA Aceh, based on monitoring undertook between 2013 and 2015, 200 Sumatran tigers are left in the wild in Aceh (Tempo). Luskin data for Leuser and Ulu Masen gives 140 + 45 adult tigers.

I have written a short Gunung Leuser National Park travel guide.

Kerinci Seblat National Park & Rimbang Baling / Batang Hari

Kerinci Seblat is the largest National Park of Sumatra. Much of the it is actually remote moutainous areas, which are virtually inaccessible, thus protected. The lowland areas are threatened by illegal logging and illegal forest conversion by small-scale farmers.

Two Tigers Protection Units were established in early 2000s in the National Park. Between 2000 and 2012, the TPCU recorded 87 poaching cases that has lead to 33 tigers killed (Rifaie 15), indicating that their presence is not enough to deter poachers.

A natural connection between Kerinci Seblat and the Rimbang Baling/Batang Hari landscapes exist but deforestation is rampant in the area and the forest corridor is far from being fully protected by a conservation status.

According to the BKSDA Riau, there would be 53 tigers in Riau (Mongabay). The best habitat for tigers in Riau would be Suaka Margaswasta Bukit Rimbang, Bukit Batu (Rimbang Baling).

A female named Rima has been caught on camera traps with 3 cubs in 2015 and 4 cubs in 2017. There is even a footage of a couple mating (took 12 years of camera trapping to get it). So this population is still breeding fairly well.

I have used many pictures from Kerinci Seblat National Park in this article. If you are interested to visit, I have written a short travel guide about the Jambi part of the NP

Sibolga & Batang Toru

The Batang Toru is under the spotlights since a moment due to a large hydroelectric dam projects ongoing.

Batang Toru is home to a population of orangutan. In 2017 this population was established as the third distinct species of orangutans.

More details about Batang Toru in the upcoming article of the series on orangutan.

Series – Conservation Status

Sources

- HarimauKita : Sumatran Tiger Conservation Forum

- Liu & al., “Genome-Wide Evolutionary Analysis of Natural History and Adaptation in the World’s Tigers”, Current Biology 28, 1-10, December 18. [featuring an interesting map of the historical range of all tiger species].

- Awesome camera traps gallery by WWF Indonesia.

- E. Sanderson & al. 2006. Setting Priorities for the Conservation and Recovery of Wild Tigers: 2005-2015. The Technical Assessment. WCS, WWF, Smithsonian, and NFWF-STF, New York and Washington, DC, USA (link).

- Shepherd, C. R. and Magnus, N. 2004. Nowhere to hide: The Trade in Sumatran Tiger (link).

- Nyhus PJ, Tilson R. 2004. Characterizing human-tiger conflict in Sumatra, Indonesia: implications for conservation. Oryx 38: 68-74 (link).

- IUCN 2008 estimates of Sumatran tigers population (link).

- Wibisono H., Pusparini W.. 2010. Sumatran tiger (Pantheratigris sumatrae): A review ofconservation status. Integrative Zoology 2010; 5: 313-323 (link).

- Rifaie & Al. 2015. Spatial point pattern analysis of the Sumatran tiger poaching cases in and around Kerinci Seblat National Park, Sumatra. Biodiversitas, Volume 16, Number 2, October 2015. Pages: 311-319 (link).

- Luskin & al. 2017. Sumatran tiger survival threatened by deforestation despite increasing densities in parks. Nature Communications (link).

- Zamzami, “Harimu Luka Kena Jeratan Terjebak di Kolong Ruko”, 18/11/2018. Mongabay (link).

- Ayat S. Karokaro, “Dua Bayi Harimau Sumatera Lahir di Barumun Sanctuary, Populasi Meningkat?”, 26/12/2018. Mongabay (link).

- Ayat S. Karokaro, “Palas, Potret Konflik Harimau dan Manusia di Sekitar Suaka Margasatwa Barumun”, 13/08/2019. Mongabay (link).

Can we in case spread the population of the Sumatran Tiger to other ASEAN Countries? Maybe create a new wildlife reserve on each ASEAN country to cater a new population of Sumatran Tigers and there prey to these areas? Create first the area to be conserve and protected and later release several male and female Tigers on these areas together with their prey. I think this would help increase the Tiger population. Is this possible?

Fantastic idea, with the obvious possibility of increasing their tiger numbers. If this works out it can hopefully inspire other Tiger countries to follow in the Sumatran tiger plan and use it to protect and increase their own tiger populations.

Hi,

Other subspecies of tigers inhabits other countries of the ASEAN (but the Philippines) and they suffer the same woes : habitat loss and fragmentation as well as poachings.

Indonesia has already huge protected areas. Actually making them true sanctuaries from deforestation and poachers would be already a huge step forward.

Great article!