The Batak people

Batak is an umbrella name used to refer to the ethnic groups of the North Sumatra highlands. Despite what guidebooks may suggest, they are not a unified people.

First of all you have 6 ethnic groups :

- The Mandailing and Angkola in the south

- The Toba in the center

- The Papak/Dairi in the northwest

- The Karo and the Simalungun in the north and northeast

Each of the group has its own language/dialect that belongs to a linguistic group. The groups are independent languages with a common origin in the past. Different dialects exist within one group but they are intelligible to each others :

- The dialects of the South : Toba, Mandaling and Angkola

- The Pakpak/Dairi

- The Karo and Simalungun

Wikipedia gives a slightly different classification (Papak/Dairi, Karo and Simalungun being similar but with some Simalungun dialect closer to Toba), but given there is no source given, I’m sticking with what is in Sibeth’s book.

Each Batak language has its own script which is most likely derived from an old Pallava script from India. It is very seldomly used nowadays (the welcoming message written on the entrance gate of Tuktuk are translated into Toba for instance). Even 50 years ago, in most villages only the guru (magician-priest) could use the Batak scripts.

Unfortunately, no Batak written sources describing life in the pre-colonial period have survived. The books and bambo texts (the pustaka) have mostly a religious content.

If you are interested in Batak manuscripts, the British Library has scanned all 37 manuscripts of its collection and uploaded them online for free here.

The old days

For centuries the Batak tribes remained rather isolated due to their surrounding environment. Until the early 20th century, wide areas of the mountain regions were still covered by primary forest. Only with the later increase of the population and the development of the timber industry, the clearing started.

Still they maintained trading contacts with the coastal region, providing them with camphor and benzoin (a resin used to make incense and perfumery) and getting supplies of salt.

Based on the few historical sources available, each of the six Batak tribes were not ruled by a single leader. Consequently, there had never been a general political unity of the Batak.

Batak did have raja (litteraly “king” in Indonesian, from Indian maharaja) but as in most parts of Indonesia, those raja ruled over a small area and had few power compared to our Western kings.

- Karo and Pakpak had a raja in most urung (the largest political units) called simply raja urung or sibayak (remember the volcano ?) but he had autorithy merely in wartime.

- The Toba had a kind of priest-king called Si Singamangaraja, a hereditary duty that was largely restricted to the religious sphere. The 12th king opposed the Dutch colonial power until he was shot dead in 1907, marking the end of the resistance of the Toba. The village chiefs in Toba were also called raja.

- The Simalungun region was divided into four smaller state each ruled by a raja governing in a near-feudal manner. The raja were appointed by the Sultan of Aceh.

Ritual cannibalism

The Batak were attributed very early in the history a reputation of cannibals that fascinated visitors at least as far back as Marco Polo in the 13th century !

It is typically assumed that the Dutch rule put a final end to these practices, as they actually did for such things as headhunting in Kalimantan or aristocrat widow burning in Bali. But in the case of the Batak there is actually very scant evidence that this cannibalism ever existed.

Early missionaries in the 19th centuries are suspected to have exaggerated if not made up testimonies in order to receive more funding for their mission (for instance by reporting that the guru were sacrificing children to prepare the magical pupuk powder).

I quote the following from historian Leonard Andaya : “lurid details of cannibalistic practices may have been provided by the Batak themselves in an effort to prevent outsiders from penetrating into their lands.

From early time, therefore, cannibalism became associated with Batak identity and had the desired effect of limiting the intrusion of European until the 19th century.

It appears that many of the comment made on Batak cannibalism were hearsay, and there is no evidence of any commentator having witnessed its occurrence. While ritual cannibalism may have been practiced as a form of punishment, to dwell on cannibal tales simply reinforces long-held misleading stereotypes about the Batak.“

Marga

Every Batak belongs to a patrilinear family group called marga in Toba and merga in Karo. A Batak must marry outside its marga and will then have a subordinate relationship towards its father-in-law family.

Batak are some of the few Indonesian people to bear a transmissible family name like we do in the Western countries (you can pick whatever you want as a first and last name for your child in Indonesia, I also wrote a dedicated article on names in Indonesia).

Traditional architecture

If you travel in the Batakland near Toba or among the Karo, you will definetely notice the traditional architecture.

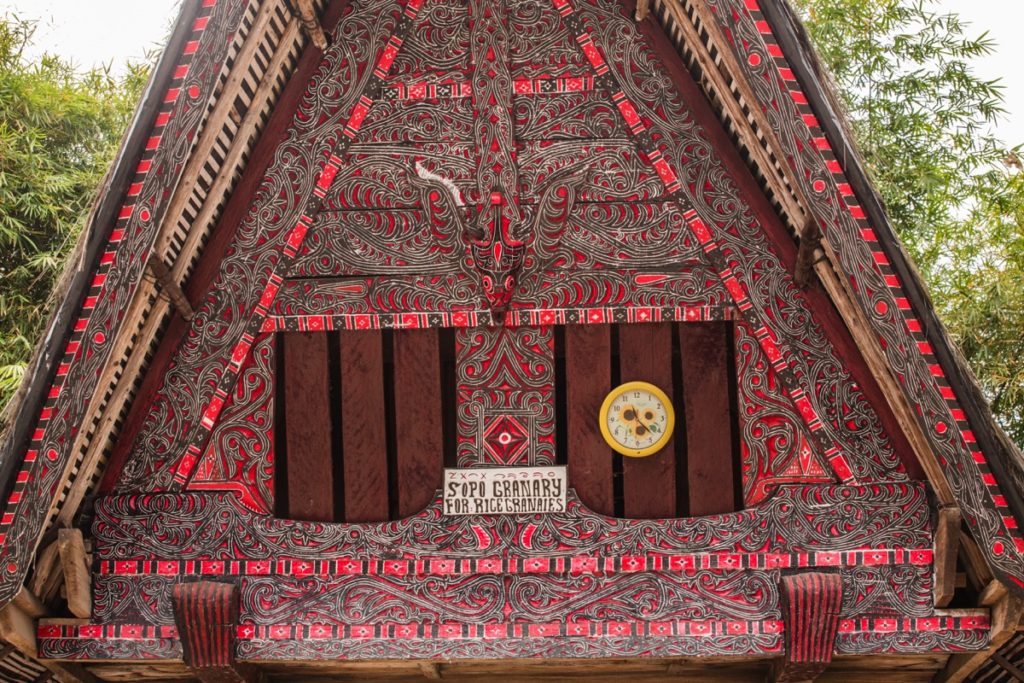

It is better preserved around Toba, with many houses still standing and several of them decorated with intricated carving (Karo house are more sparsely decorated). The saddle-shaped roof is reminescent of the architectures found in West Sumatra or Toraja.

Toba traditional villages are usually organized as a line of houses (jabu) facing granaries (sopo). In the last decades, virtually all sopo have either collapsed or have been converted into dwellings.

According to Sibeth, from the 1920s corrugated iron became increasingly used to build the roofs with the support of the Dutch. Today the only Toba houses standing with a roof made of sugarpalm fiber (ijuk) I know are the ones from the museum in Samanindo.

If you pay close attention when strolling Toba area, you’ll notice that many houses have a concrete extension built in the back, usually equipped with running water and used as a bathroom and kitchen.

Traditional large houses were inhabited by several families. Two of them can be seen for instance in Lingga village near Berastagi, but they are in quite poor shape inside and most of its former inhabitants have chosen to build an individual house nearby.

In times of war, the traditional house with its doors and windows closed offered a good protection against ennemies unless fire was set to the roof. The outside decoration served also to ward off evil bégu or hantu (ghosts), as well as human black magic.

The building of a house was accompanied by different religious ceremonies supposed to bring an harmonious atmosphere among the different families set to move in. These ceremonies were forbidden by the Christian church and the building of individual houses similar to the one’s of the coastal Malay was encouraged.

It is also true that concrete houses are less prone to fire and easier to built for a single family (erecting a large wooden house is a serious undertaking).

Traditional costumes

Nowadays, wedding are the main occasion to see people wearing the traditional Batak clothes (for a broader gallery covering all Indonesia, check my Indonesian Costumes gallery)

Batak Toba

Batak Mandailing

Batak Karo

Religion

From traditional religion to Christianity and Islam

Toba Batak has been converted by German missionaries from 1864, but the movement accelerated from the murder of the 12th “priest-king” of Toba in 1907. Karo Batak shift towards Christianism (mostly Protestantism) occured much later.

According to Sibeth, in 1980 57% of the Karo adhered to the traditional religion (perbégu or pemana). In the early 90s, they were still 20%, a collapse that have continued until today.

Some small communities adhering to the old parmalim religion (recognized since the 1970s as a sect of Hinduism by the government) can still be found on the south shore of Lake Toba.

The old religion of Toba and Karo have been abundantly described by the missionaries and the colonial administration. Very little is known on the other hand on the traditional religion of the Pakpak and the Simalungun.

Islamized Batak : Mandailing and Angkola

Mandailing and Angkola were converted to Islam in the mid 19th century, in the wake of the Padri wars originating from modern-day West Sumatra. According to Sibeth, “Islamized Batak lost their cultural identity and largely assimilated with the culture of their more powerful neighbours. Today, only the family names have not been completely discarded. In the case of the Mandailing such was the rejection of Batak culture and the loss of cultural identity that they denied that they were related to the other Batak and set great store by not being called Batak“.

Only by looking at old pictures from the Dutch colonial archives, one can see that a few centuries ago, those southern Batak tribe had much in common with their cousins when it comes to architecture or traditional outfit for instance.

Origin myth

In Toba

At the beginning there was only the sky, inhabited by the gods, and the great sea beneath, home of the mighty dragon of the underworld Naga Padoha.

The creation of everything is related to a god of uncertain origin Mula Jadi Na Bolon ‘beginning of becoming’. He has 3 sons born from eggs laid by a hen fertilized by Mula Jadi and also begets 3 daughters that he gives to his son as wives. Other gods exist like the water goddess Boru Saniang Naga or the fertility god Boraspati Ni Tano.

One of the son is Batara Guru who has a daughter called Si Boru Beak Parujar. Another son is Mangalabulan who has a ugly son who looks like a lizard. The plan is to marry them but the daughter of Batara Guru refuses and flees on the middle world which was still a great ocean back then.

Out of compassion, Mula Jadi sends some earth to her granddaughter so that she can live on it. She spreads the earth but disturbs Naga Pahoda in the process, they fight and eventually defeat the dragon.

Si Boru Deak Purajar then marries her promised husband and has twins (2 boys and 2 girls). The twins settle on Pusuk Buhit where they found the mythical village of origin of the Toba Batak. Their grandson is Si Raja Batak, the common ancestor of all modern Toba Batak.

In Karo

In Karo, as well as in Toba, the gods were rather unimportant in religious life. They don’t receive sacrifices for instance. Actually the knowledge about the gods and the myths is mostly preserved in the lore of the guru (magician-priest).

Still, they recognize Batara Guru as the most senior god. But they consider that Earth was created by his son Tuana Banua Koling.

The major elements of the Karo traditional religion was the worship of the ancestors and the natural spirits.

The concept of tendi

The concept of tendi (Karo term, the Toba use the word tondi) is central in the Batak old religion. Sibeth translates it as ‘life-soul’ and the connected concept of bégu as ‘death-soul’.

Tendi is given by the gods before birth. The tendi itself decides the destiny of the individual at its inception. Sibeth reports different myth relating this event that he collected from missionaries writings. One of them (from Toba) says that near Mula Jadi in the upper world grows a tree called Djambubarus which has all the possible fates of a person written on its leaves. Before descending to Earth, a tondi has to pick a leave first. Whatever is written on the leaf chosen will be its destiny.

The Toba consider that a person has 7 tondi, but 5 of them are rather minor. The second tondi is found in the placenta of the newborn, that is usually buried under the house and called saudara (‘sibling’). It is regarded as the newborn’s guardian spirit.

Karo usually consider the placenta as the source of guardian spirit but they usually said that only the guru (magician-priest) have 7 tendi while normal people have only one.

Tendi can live outside the body for a time, this is regarded as the main source of sickness. Traditional methods of healing aimed at bringing the tendi back into the body. Black magic is also capable of separating the tendi for the body.

At death, the tendi disappears and the bégu (‘death soul’) is set free. Sibeth explains that it is not clear if the bégu is an aspect of the tendi or its mere transformation. Batak believe that bégu continue to live near their previous home and influence the life of the livings.

The cult of the dead

Bad dreams or misfortune may be signs that the bégu of an ancestor is not satisfied. It can be soothed by offerings and prayers first. If it doesn’t work, it is up to a guru or a medium to contact the bégu and find out what it wants.

By great ceremonies reminiscent of the one in Toraja, a bégu could access an improved status called sumangot and latter sumbaon.

In Karo, the living had to ensure the status of their ancestors bégu by the mean of offerings (bégu are believed to share the livings offering in the village of the dead and derives status from that). The bégu were not immortal yet but were thought to die 7 times before changing into a straw and finally becoming earth.

Method of burials among the Batak were not uniform but there was usually a reburial ceremony performed after at least one generation by rich families. Such ceremonies are still performed today in Toba, usually in June and December. On this occasion, bones are exhumed, cleaned and mourned before being placed in a bone house.

Prestigious individuals could be put to rest in a stone sarcophagus carved as the mythological singa. Nowadays, rich families still build ossuaries but they use a Indonesian word to call it : tugu (memorial) probably to dissociate it from the old religion. An impressive tugu shows the power and the prestige of a marga.

Some sub-clans of the merga Sembiring in Karo do let the river carry away the ashes of their deceased. Most of them until today keep the bones of their ancestors in ossuaries called geriten.

Every Toba is burried. In the past, mask dances were often performed at funerals. It was considered a great misfortune to die without male heir, because only their offerings can bring prestige to the bégu in the afterworld. The jointed dole (gale-gale) and the associated dances which are now a tourist attraction in Samosir was originaly made to be substituted to the male sons of someone who would outlive its sons.

Magic

Guru were the magician-priests of the Karo, leading rituals, healing diseases, telling the fortune and mediating with the spirits. He has extensive knowledge about the traditional myths, the plants to use and the rituals. The guru was often the only one in the village able to read the Batak script and also the keeper of the literary cultural heritage.

The Toba call them datu.

In both regions, most of the guru were only able to make a given sort of medecine or to carry out a few rituals.

In Sibeth’s book you will find fascinating descriptions of how guru in the 90s were bringing tendi back by playing the flute or reciting mantras, negociating peace with spirits or engaging them with a war dance.

He also tells how already 30 years ago most the guru were marginalized and regarded by most inhabitants as crooks. This change of attitude towards the old religion happened in the course of only one generation.

Sources

- Achim Sibeth – The Batak : peoples of the island of Sumatra : living with ancestors, 1991.

- Wikipedia has very good articles about the Batak, the related articles about Batak sub-ethnic groups are also worth reading.

- Leonard Anday – Leaves of the Same Tree. Trade and Ethnicity in the Straits of Melaka, 2010.

Your article on so-called Batak cannibalism is ahistorical and pure hoax! All Western foreigners that wrote about it NEVER really saw any act of cannibalism done by the Batak; all just hearsay. If you understand the kinship system of the Batak called Marga and Dalihan Natolu then you won’t recycle colonial and the German missionary bullshit about us Batak. Do your homeworl and read academic writings on Batak culture instead of recycling orientalist craps!

Dear Saut.

Thank you for your comment, which is, I must say, on point.

I looked a bit for some books on the topic and I came across Leonard Andaya’s “Leaves from the Same Tree” which is absolutely excellent. I guess I wouldn’t have researched this topic again without your comment. Thank you again.

Any other good books you would like to recommend ?

I updated the concerned section of the article.

For anyone reading your comment in the future, I save below the original passage you commented :

“Cannibalism was practiced by the Batak but its frequency was often overestimated. It was regarded as a judicial act restricted to a few crimes (mostly thief, adultery, treason and spying).

It is likely that the Batak created for themselve an inflated reputation to scare their ennemies.

In 1834, two American missionaries (Munson and Lyman) were indeed murdered and presumably eaten. Yet, the early missionaries in general are also suspected to have exaggerated some details of their testimonies to receive more fundings for their mission (for instance explaining that the guru were sacrificing children to prepare the magical pupuk powder, while the study of the preserved pustaka explaining the “recipe” found no mention of it).

It is certain that the colonial Dutch government and the presence of the missionaries were instrumental to put a full stop to cannibalism.”

I believe that our ancestor didn’t do any canibalism activity. We never know what happened back then, but I do believe they create that story to defense their teritory and their people from another ethnic or foreign. Even Marcopolo refused to visit because he heard some information about it. Before christianity exist in batak land, they had religion and we respect life that much, and even when people die, we make ceremony to keep their skeleton re-unite with their family and ancestor known with mangukol holi. Believe it or not, we have so much thing to eat from nature. We have our authentic spice, which means we like to explore cuisine. We have our own letter, which means our ancestor spread the canibalism on purpose. In batak language, there are many principles. And some of the words on that showing about love and respect such as “elek, holong, burju” So I don’t get it if many western literacy say so!

Jika kau mencoba untuk meluruskan sesuatu, lakukan itu mulai dari hal yang terkecil. Elek, Holong, Burju itu bahasa batak TOBA, jgn bilang bahasa batak karena banyak bahasa batak. Gara-gara cara seperti inilah mengapa orang-orang melihat hal-hal yang berkaitan dengan batak TOBA langsung dianggap Batak semuanya. Padahal Batak itu bukan hanya batak TOBA. Jadi, coba benahi dulu dari diri sendiri ya.

armalim or Malim is the modern form of the Batak Toba religion. Practitioners of Malim are called Parmalim.

At the end of the 19th and in the beginning of the 20th century the Parmalim movement, which originated in Toba lands spread to other areas of the Batak lands. Especially in the lower Karo lands, the ‘dusun’ the Malim religion, became very influential as an expression of anti-colonial sentiments at the turn of the 20th century. Today the majority of Parmalim are Toba Batak. The largest of the several existing Parmalim groups has its centre in Huta Tinggi in the vicinity of Laguboti on the south shore of Lake Toba.

Non-Malim Batak peoples (those following Christian or Muslim faith) often continue to believe certain aspects of traditional Batak spiritual belief.

“All Western foreigners that wrote about it NEVER really saw any act of cannibalism done by the Batak”, yess, i do agree.

I am also Batak, and appreciate with your introduction article, canibalism is there and I am not ashamed of it because it is taken long time ago, my parents and my elder also tell me about it. Batak people currently have a major parts in Indonesia life and spreading all over without eating other people and fortunately Batak people known as a community which is very well educated and religious (HKBP; Huria Kristen Batak Protestan) is the 2n largest church after Roman Catholic in Indonesia.Again thanks you

1985, I was working in Medan. A couple of my colleges was Batak. When I went to visit lake Toba I tried too convince my driver to take me further to see where the Batak people lived. The driver almost refused to take me there. He was really scared by the Batak people. I knew about there reputation to be real brutal against their enemies but I didnt expect it to be this brutal.

Anyhow we went to a Batak village and was very well received in the village. I had during that time learned a few word of the Batak language. Now I only remember the word “Horas”.

Pernahkah kamu memdengar letusan gunung Toba?

Kamu tau fosil tertua dari suku kerinci di Sumatera?

Peradaban manusia sesungguhnya dimulai dari sini.